Starting with Data

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 5 minQuestions

What is a data.frame?

How can I read a complete csv file into R?

How can I get basic summary information about my dataset?

How are dates represented in R and how can I change the format?

Objectives

Load external data from a .csv file into a data frame.

Install and load packages.

Describe what a data frame is.

Summarize the contents of a data frame.

Use indexing to subset specific portions of data frames.

Describe what a factor is.

Convert between strings and factors.

Reorder and rename factors.

Change how character strings are handled in a data frame.

Format dates.

Loading the Survey Data

library(palmerpenguins)

data(package = 'palmerpenguins')

In this palmerpenguins package, there are two datasets. ‘penguins’ is a simplified version of the raw data, curated for instructional use. Throughout the workshop though, we will also work with the raw data, ‘penguins_raw’.

This dataset is hosted by Palmer Station Antarctica LTER, a member of the Long Term Ecological Research Network. You may also learn more about the research and methodology of this particular dataset: Ecological sexual dimorphism and environmental variability within a community of Antarctic penguins (genus Pygoscelis).

Artwork by @allison_horst

Artwork by @allison_horst

Data Moment: Packages Citation

To get the package’s citation for publication, we can use the

citation()function and input the name of the package,"palmerpenguins".citation("palmerpenguins")Citation increases reproducibility, which benefits both users and producers. Along with getting the proper credit, citations helps producers keep a bibliographic record of publications and usage which references the cited tools and data.

Because datasets are easier to find with consistent, proper citation of packages and data citation, this practice also encourages reuse of the data for new studies.

This data was originally published in:

Gorman KB, Williams TD, Fraser WR (2014). Ecological sexual dimorphism and environmental variability within a community of Antarctic penguins (genus Pygoscelis). PLoS ONE 9(3):e90081. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090081

The dataset is stored as a comma separated value (CSV) file. Each row holds information for a date, and the attributes information can be found in the help:

?penguins

?penguins_raw

Artwork by @allison_horst

Artwork by @allison_horst

Reading the Data into R

The file should be downloaded to the destination you specified. R has not

yet loaded the data from the file into memory. To do this, we can use the

read_csv() function from the tidyverse package.

Packages in R are basically sets of additional functions that let you do more

stuff. The functions we’ve been using so far, like round(), sqrt(), or c()

come built into R. Packages give you access to additional functions beyond base R.

A similar function to read_csv() from the tidyverse package is read.csv() from

base R. We don’t have time to cover their differences but notice that the exact

spelling determines which function is used.

Before you use a package for the first time you need to install it on your

machine, and then you should import it in every subsequent R session when you

need it.

To install the tidyverse package, we can type

install.packages("tidyverse") straight into the console. In fact, it’s better

to write this in the console than in our script for any package, as there’s no

need to re-install packages every time we run the script.

Then, to load the package type:

library(tidyverse)

Now we can use the functions from the tidyverse package.

Let’s use read_csv() to read the data into a data frame

(we will learn more about data frames later):

penguins <- read.csv(path_to_file("penguins.csv"))

If you have a csv file, you may use read_csv to create an object with it. path_to_file() is not nesessary to use read_csv().

When you execute read_csv on a data file, it looks through the first 1000 rows

of each column and guesses its data type. For example, in this dataset,

read_csv() reads flipper_length_mm as int (a numeric data type), and species

as char. You have the option to specify the data type for a column

manually by using the col_types argument in read_csv.

We can see the contents of the first few lines of the data by typing its

name: penguins. By default, this will show you as many rows and columns of

the data as fit on your screen.

If you wanted the first 50 rows, you could type print(penguins, n = 50)

We can also extract the first few lines of this data using the function

head():

head(penguins)

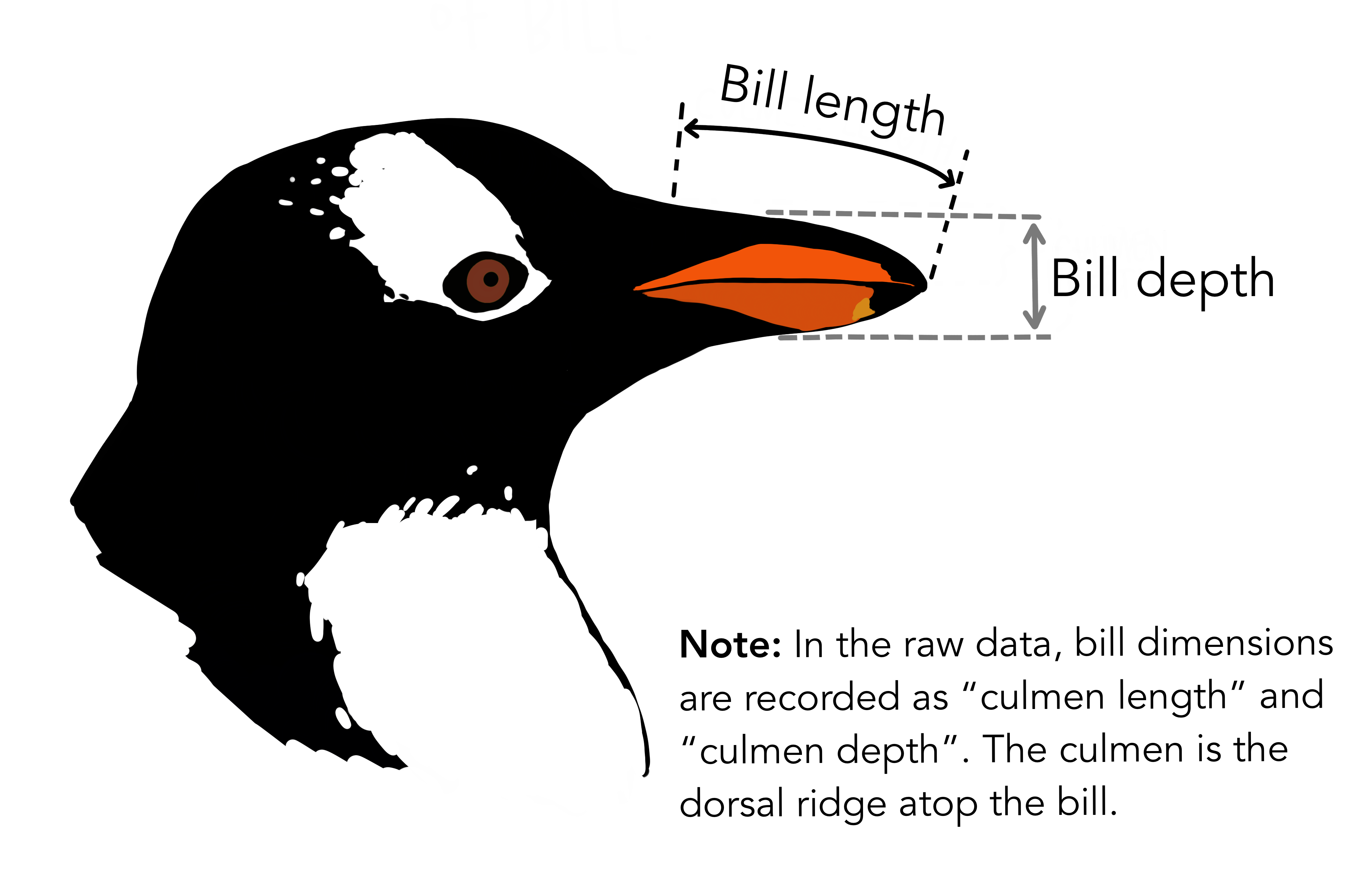

species island bill_length_mm bill_depth_mm

1 Adelie Torgersen 39.1 18.7

2 Adelie Torgersen 39.5 17.4

3 Adelie Torgersen 40.3 18.0

4 Adelie Torgersen NA NA

5 Adelie Torgersen 36.7 19.3

6 Adelie Torgersen 39.3 20.6

flipper_length_mm body_mass_g sex year

1 181 3750 male 2007

2 186 3800 female 2007

3 195 3250 female 2007

4 NA NA <NA> 2007

5 193 3450 female 2007

6 190 3650 male 2007

Unlike the print() function, head() returns the extracted data. You could

use it to assign the first 100 rows of penguins to an object using

penguins_sample <- head(penguins, 100). This can be useful if you want to try

out complex computations on a subset of your data before you apply them to the

whole data set.

There is a similar function that lets you extract the last few lines of the data

set. It is called (you might have guessed it) tail().

To open the dataset in RStudio’s Data Viewer, use the view() function:

view(penguins)

Note

read_csv()assumes that fields are delineated by commas. However, in several countries, the comma is used as a decimal separator and the semicolon (;) is used as a field delineator. If you want to read in this type of files in R, you can use theread_csv2()function. It behaves likeread_csv()but uses different parameters for the decimal and the field separators. There is also theread_tsv()for tab separated data files andread_delim()for less common formats. Check out the help forread_csv()by typing?read_csvto learn more.In addition to the above versions of the csv format, you should develop the habits of looking at and recording some parameters of your csv files. For instance, the character encoding, control characters used for line ending, date format (if the date is not split into three variables), and the presence of unexpected newlines are important characteristics of your data files. Those parameters will ease up the import step of your data in R.

What are Data Frames?

When we loaded the data into R, it got stored as an object of class tibble,

which is a special kind of data frame (the difference is not important for our

purposes, but you can learn more about tibbles

here).

Data frames are the de facto data structure for most tabular data, and what we

use for statistics and plotting.

Data frames can be created by hand, but most commonly they are generated by

functions like read_csv(); in other words, when importing

spreadsheets from your hard drive or the web.

A data frame is the representation of data in the format of a table where the columns are vectors that all have the same length. Because columns are vectors, each column must contain a single type of data (e.g., characters, integers, factors). For example, here is a figure depicting a data frame comprising a numeric, a character, and a logical vector.

We can see this also when inspecting the structure of a data frame

with the function

str():

str(penguins)

Inspecting Data Frames

We already saw how the functions head() and str() can be useful to check the

content and the structure of a data frame. Here is a non-exhaustive list of

functions to get a sense of the content/structure of the data. Let’s try them out!

- Size:

dim(penguins)- returns a vector with the number of rows in the first element, and the number of columns as the second element (the dimensions of the object)nrow(penguins)- returns the number of rowsncol(penguins)- returns the number of columns

- Content:

head(penguins)- shows the first 6 rowstail(penguins)- shows the last 6 rows

- Names:

names(penguins)- returns the column names (synonym ofcolnames()fordata.frameobjects)rownames(penguins)- returns the row names

- Summary:

str(penguins)- structure of the object and information about the class, length and content of each columnsummary(penguins)- summary statistics for each column

Note: most of these functions are “generic”, they can be used on other types of

objects besides data.frame.

Challenge

Based on the output of

str(penguins), can you answer the following questions?

- What is the class of the object

penguins?- How many rows and how many columns are in this object?

Solution

Data Moment: Stuctures

When we look at the stucture of the raw data, we see that it holds 344 observations and 17 variables:

Indexing and Subsetting data frames

Our penguins data frame has rows and columns (it has 2 dimensions). In practice, we may not need the entire data frame; for instance, we may only be interested in a subset of the observations (the rows) or a particular set of variables (the columns). If we want to extract some specific data from it, we need to specify the “coordinates” we want from it. Row numbers come first, followed by column numbers.

# We can extract specific values by specifying row and column indices

# in the format:

# data_frame[row_index, column_index]

# For instance, to extract the first row and column from penguins:

penguins[1, 1]

# First row, fifth column:

penguins[1, 8]

# We can also use shortcuts to select a number of rows or columns at once

# To select all columns, leave the column index blank

# For instance, to select all columns for the first row:

penguins[1, ]

# The same shortcut works for rows --

# To select the first column across all rows:

penguins[, 1]

# An even shorter way to select first column across all rows:

penguins[1] # No comma!

# To select multiple rows or columns, use vectors!

# To select the first three rows of the 5th and 6th column

penguins[c(1, 2, 3), c(5, 6)]

# We can use the : operator to create those vectors for us:

penguins[1:3, 5:6]

# This is equivalent to head_penguins <- head(penguins)

head_penguins <- penguins[1:6, ]

# As we've seen, when working with tibbles

# subsetting with single square brackets ("[]") always returns a data frame.

# If you want a vector, use double square brackets ("[[]]")

# For instance, to get the first column as a vector:

penguins[[1]]

# To get the first value in our data frame:

penguins[[1, 1]]

: is a special function that creates numeric vectors of integers in increasing

or decreasing order, test 1:10 and 10:1 for instance.

You can also exclude certain indices of a data frame using the “-” sign:

penguins[, -1] # The whole data frame, except the first column

penguins[-(7:nrow(penguins)), ] # Equivalent to head(penguins)

Data frames can be subset by calling indices (as shown previously), but also by calling their column names directly:

# As before, using single brackets returns a data frame:

penguins["species"]

penguins[, "species"]

# Double brackets returns a vector:

penguins[["species"]]

# We can also use the $ operator with column names instead of double brackets

# This returns a vector:

penguins$species

In RStudio, you can use the autocompletion feature to get the full and correct names of the columns.

Exercise

Create a

data.frame(penguins_200) containing only the data in row 200 of thepenguinsdataset.Notice how

nrow()gave you the number of rows in the data frame?

- Use that number to pull out just that last row in the data frame.

- Compare that with what you see as the last row using

tail()to make sure it’s meeting expectations.- Pull out that last row using

nrow()instead of the row number.- Create a new data frame (

penguins_last) from that last row.Use

nrow()to extract the row that is in the middle of the data frame. Store the content of this row in an object namedpenguins_middle.Combine

nrow()with the-notation above to reproduce the behavior ofhead(penguins), keeping just the first through 6th rows of the penguins dataset.Solution

Factors

When we did str(penguins) we saw that several of the columns consist of

integers. The columns species, island, sex, however, are

of the class character.

Arguably, these columns contain categorical data, that is, they can only take on

a limited number of values.

R has a special class for working with categorical data, called factor.

Factors are very useful and actually contribute to making R particularly well

suited to working with data. So we are going to spend a little time introducing

them.

Once created, factors can only contain a pre-defined set of values, known as levels. Factors are stored as integers associated with labels and they can be ordered or unordered. While factors look (and often behave) like character vectors, they are actually treated as integer vectors by R. So you need to be very careful when treating them as strings.

When importing a data frame with read_csv(), the columns that contain text are not automatically coerced (=converted) into the factor data type, but once we have

loaded the data we can do the conversion using the factor() function:

#create a variable that consists of two levels

low_hi <- c("low", "high", "low", "high")

summary(low_hi)

#using factor conversion

low_hi <- factor(low_hi)

We can see that the conversion has worked by using the summary()

function again. This produces a table with the counts for each factor level:

summary(low_hi)

high low

2 2

R will assign 1 to the level "high" and 2 to the level "low" (because

h comes before l, even though the first element in this vector is

"low"). You can see this by using the function levels() and you can find the

number of levels using nlevels():

levels(low_hi)

nlevels(low_hi)

Sometimes, the order of the factors does not matter, other times you might want

to specify the order because it is meaningful (e.g., “low”, “medium”, “high”),

it improves your visualization, or it is required by a particular type of

analysis. Here, one way to reorder our levels in the class vector would be:

low_hi # current order

low_hi <- factor(class, levels = c("low", "high"))

low_hi # after re-ordering

In R’s memory, these factors are represented by integers (1, 2, 3), but are more

informative than integers because factors are self describing: "low",

"high" is more descriptive than 1, 2. Which one is “low”? You wouldn’t

be able to tell just from the integer data. Factors, on the other hand, have

this information built in. It is particularly helpful when there are many levels.

Challenge

Change the columns

speciesandislandin thepenguinsdata frame into a factor.Using the functions you learned before, can you find out… How many rows contain Adelie species?

How many different islands did the research record at?

Solution

Converting factors

If you need to convert a factor to a character vector, you use

as.character(x).

as.character(low_hi)

In some cases, you may have to convert factors where the levels appear as

numbers (such as concentration levels or years) to a numeric vector. For

instance, in one part of your analysis the years might need to be encoded as

factors (e.g., comparing average weights across years) but in another part of

your analysis they may need to be stored as numeric values (e.g., doing math

operations on the years). This conversion from factor to numeric is a little

trickier. The as.numeric() function returns the index values of the factor,

not its levels, so it will result in an entirely new (and unwanted in this case)

set of numbers. One method to avoid this is to convert factors to characters,

and then to numbers.

Another method is to use the levels() function. Compare:

year_fct <- factor(c(1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995))

as.numeric(year_fct) # Wrong! And there is no warning...

as.numeric(as.character(year_fct)) # Works...

as.numeric(levels(year_fct))[year_fct] # The recommended way.

Notice that in the levels() approach, three important steps occur:

- We obtain all the factor levels using

levels(year_fct) - We convert these levels to numeric values using

as.numeric(levels(year_fct)) - We then access these numeric values using the underlying integers of the

vector

year_fctinside the square brackets

as.numeric(year_fct) # Wrong! And there is no warning...

3 1 2 4 5

as.numeric(as.character(year_fct)) # Works...

[1] 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995

as.numeric(levels(year_fct))[year_fct] # The recommended way.

[1] 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995

Notice that in the recommended levels() approach, three important steps occur:

- We obtain all the factor levels using

levels(year_fct) - We convert these levels to numeric values using

as.numeric(levels(year_fct)) - We then access these numeric values using the underlying integers of the

vector

year_fctinside the square brackets

Renaming factors

When your data is stored as a factor, you can get a quick glance at the number of observations represented by each factor level. Let’s look at the number of males and females observed:

penguins$sex <- factor(penguins$sex)

plot(penguins$sex)

However, as we saw when we used summary(surveys$sex), there are 11 individuals for which the sex information hasn’t been recorded. To show them in the plot, we can turn the missing values into a factor level with the addNA() function. We will also have to give the new factor level a label. We are going to work with a copy of the sex column, so we’re not modifying the working copy of the data frame:

sex <- surveys$sex

levels(sex)

sex <- addNA(sex)

levels(sex)

head(sex)

levels(sex)[3] <- "undetermined"

levels(sex)

Now we can plot the data again, using plot(sex).

Challenge:

Rename “F” and “M” to “female” and “male” respectively. Now that we have renamed the factor level to “undetermined”, can you recreate the barplot such that “undetermined” is first (before “female”)?

Solution

Challenge

We have seen how data frames are created when using the

read.csv(), but they can also be created by hand with thedata.frame()function. There are a few mistakes in this hand-crafteddata.frame, can you spot and fix them? Don’t hesitate to experiment!animal_data <- data.frame(animal = c("dog", "cat", "sea cucumber", "sea urchin"), feel = c("furry", "squishy", "spiny"), weight = c(45, 8 1.1, 0.8))## Challenge: ## There are a few mistakes in this hand-crafted `data.frame`, ## can you spot and fix them? Don't hesitate to experiment! animal_data <- data.frame(animal = c(dog, cat, sea cucumber, sea urchin), feel = c("furry", "squishy", "spiny"), weight = c(45, 8 1.1, 0.8))Can you predict the class for each of the columns in the following example? Check your guesses using

str(country_climate):

- Are they what you expected? Why? Why not?

- What would have been different if we had added

stringsAsFactors = FALSEto this call?- What would you need to change to ensure that each column had the accurate data type?

country_climate <- data.frame( country = c("Canada", "Panama", "South Africa", "Australia"), climate = c("cold", "hot", "temperate", "hot/temperate"), temperature = c(10, 30, 18, "15"), northern_hemisphere = c(TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, "FALSE"), has_kangaroo = c(FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, 1) )## Challenge: ## Can you predict the class for each of the columns in the following ## example? ## Check your guesses using `str(country_climate)`: ## * Are they what you expected? Why? why not? ## * What would have been different if we had added `stringsAsFactors = FALSE` ## to this call? ## * What would you need to change to ensure that each column had the ## accurate data type? country_climate <- data.frame(country = c("Canada", "Panama", "South Africa", "Australia"), climate = c("cold", "hot", "temperate", "hot/temperate"), temperature = c(10, 30, 18, "15"), northern_hemisphere = c(TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, "FALSE"), has_kangaroo = c(FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, 1))Solution

Formatting Dates

A common issue that new (and experienced!) R users have is converting date and time information into a variable that is suitable for analyses. One way to store date information is to store each component of the date in a separate column. Using str(), we can confirm that our data frame does indeed have a separate column for day, month, and year, and that each of these columns contains integer values.

str(penguins)

We are going to use the ymd() function from the package lubridate (which belongs to the tidyverse; learn more here). lubridate gets installed as part as the tidyverse installation. When you load the tidyverse (library(tidyverse)), the core packages (the packages used in most data analyses) get loaded. lubridate however does not belong to the core tidyverse, so you have to load it explicitly with library(lubridate)

Start by loading the required package:

library(lubridate)

The lubridate package has many useful functions for working with dates. These can help you extract dates from different string representations, convert between timezones, calculate time differences and more. You can find an overview of them in the lubridate cheat sheet.

Let’s create an object and inspect the structure:

str("2022-01-01")

chr "2022-01-01"

Note that R reads this as a character. Now let’s paste the year, month, and day separately - we get the same result:

# sep indicates the character to use to separate each component

str(paste("2022", "01", "01", sep = "-"))

chr "2022-1-1"

Here we will use the function ymd(), which takes a vector representing year, month, and day, and converts it to a Date vector. Date is a class of data recognized by R as being a date and can be manipulated as such. The argument that the function requires is flexible, but, as a best practice, is a character vector formatted as “YYYY-MM-DD”.

my_date <- ymd(paste("2022", "01", "01", sep = "-"))

str(my_date)

Now lets look at the penguines_raw dataset and extract the column Date Egg.

egg_dates <- penguins_raw$`Date Egg`

str(egg_dates)

Let’s extract our Date Egg column and inspect the structure.

What is “Date Egg”?

?penguins_raw

We are able to pull the year, month, and day from the date values:

egg_yr <- year(egg_dates)

egg_mo <- month(egg_dates)

egg_day <- day(egg_dates)

When we imported the data in R, read_csv() recognized that this column

contained date information. We can use the day(), month() and year()

functions to extract this information from the date, and create new columns in

our data frame to store it:

# we can create dataframes

egg_dates_df <- data.frame(year = egg_yr, month = egg_mo, day = egg_day)

egg_dates_df

year month day

1 2007 11 11

2 2007 11 11

3 2007 11 16

4 2007 11 16

5 2007 11 16

...

These character vectors can be used as the argument for ymd():

ymd(paste(egg_dates_df$year, egg_dates_df$month, egg_dates_df$day, sep = "-"))

In our example above, the Date Egg column was read in correctly as a

Date variable but generally that is not the case. Date columns are often read

in as character variables and one can use the as_date() function to convert

them to the appropriate Date/POSIXctformat.

Let’s say we have a vector of dates in character format:

char_dates <- c("01/01/2020", "02/02/2020", "03/03/2020")

str(char_dates)

chr [1:3] "01/01/2020" "02/02/2020" "03/03/2020"

We can convert this vector to dates as :

as_date(char_dates, format = "%m/%d/%Y")

[1] "2012-07-31" "2014-08-09" "2016-04-30"

Argument format tells the function the order to parse the characters and

identify the month, day and year. The format above is the equivalent of

mm/dd/yyyy. A wrong format can lead to parsing errors or incorrect results.

For example, observe what happens when we use a lower case y instead of upper case Y for the year.

as_date(char_dates, format = "%m/%d/%y")

[1] "2020-01-01" "2020-02-02" "2020-03-03"

Here, the %y part of the format stands for a two-digit year instead of a

four-digit year, and this leads to parsing errors.

Or in the following example, observe what happens when the month and day elements of the format are switched.

as_date(char_dates, format = "%d/%m/%y")

[1] NA "2020-09-08" NA

Since there is no month numbered 30 or 31, the first and third dates cannot be parsed.

We can also use functions ymd(), mdy() or dmy() to convert character

variables to date.

mdy(char_dates)

Data Package Citation

Horst AM, Hill AP, Gorman KB (2020). palmerpenguins: Palmer Archipelago (Antarctica) penguin data. R package version 0.1.0. https://allisonhorst.github.io/palmerpenguins/

Key Points

Use read_csv to read tabular data in R.

Use factors to represent categorical data in R.