Ethics & Legality of Web Scraping

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

When is web scraping OK and when is it not?

Is web scraping legal? Can I get into trouble?

What are some ethical considerations to make?

What can I do with the data that I’ve scraped?

Objectives

Wrap things up

Discuss the legal and ethical implications of web scraping

Establish a code of conduct

Now that we have seen several different ways to scrape data from websites and are ready to start working on potentially larger projects, we may ask ourselves whether there are any legal and ethical implications of writing a piece of computer code that downloads information from the Internet.

In this section, we will be discussing some of the issues to be aware of when scraping websites, and we will establish a code of conduct (below) to guide our web scraping projects.

This section does not constitute legal advice

Please note that the information provided on this page is for information purposes only and does not constitute professional legal advice on the practice of web scraping.

If you are concerned about the legal implications of using web scraping on a project you are working on, it is probably a good idea to seek advice from a professional, preferably someone who has knowledge of the intellectual property (copyright) legislation in effect in your country.

Don’t break the web: Denial of Service attacks

The first and most important thing to be careful about when writing a web scraper is that it typically involves querying a website repeatedly and accessing a potentially large number of pages. For each of these pages, a request will be sent to the web server that is hosting the site, and the server will have to process the request and send a response back to the computer that is running our code. Each of these requests will consume resources on the server, during which it will not be doing something else, like for example responding to someone else trying to access the same site.

If we send too many such requests over a short span of time, we can prevent other “normal” users from accessing the site during that time, or even cause the server to run out of resources and crash.

In fact, this is such an efficient way to disrupt a web site that hackers are often doing it on purpose. This is called a Distributed Denial of Service (DoS) attack.

Distributed Denial of Service Attacks in 2020 and 2021

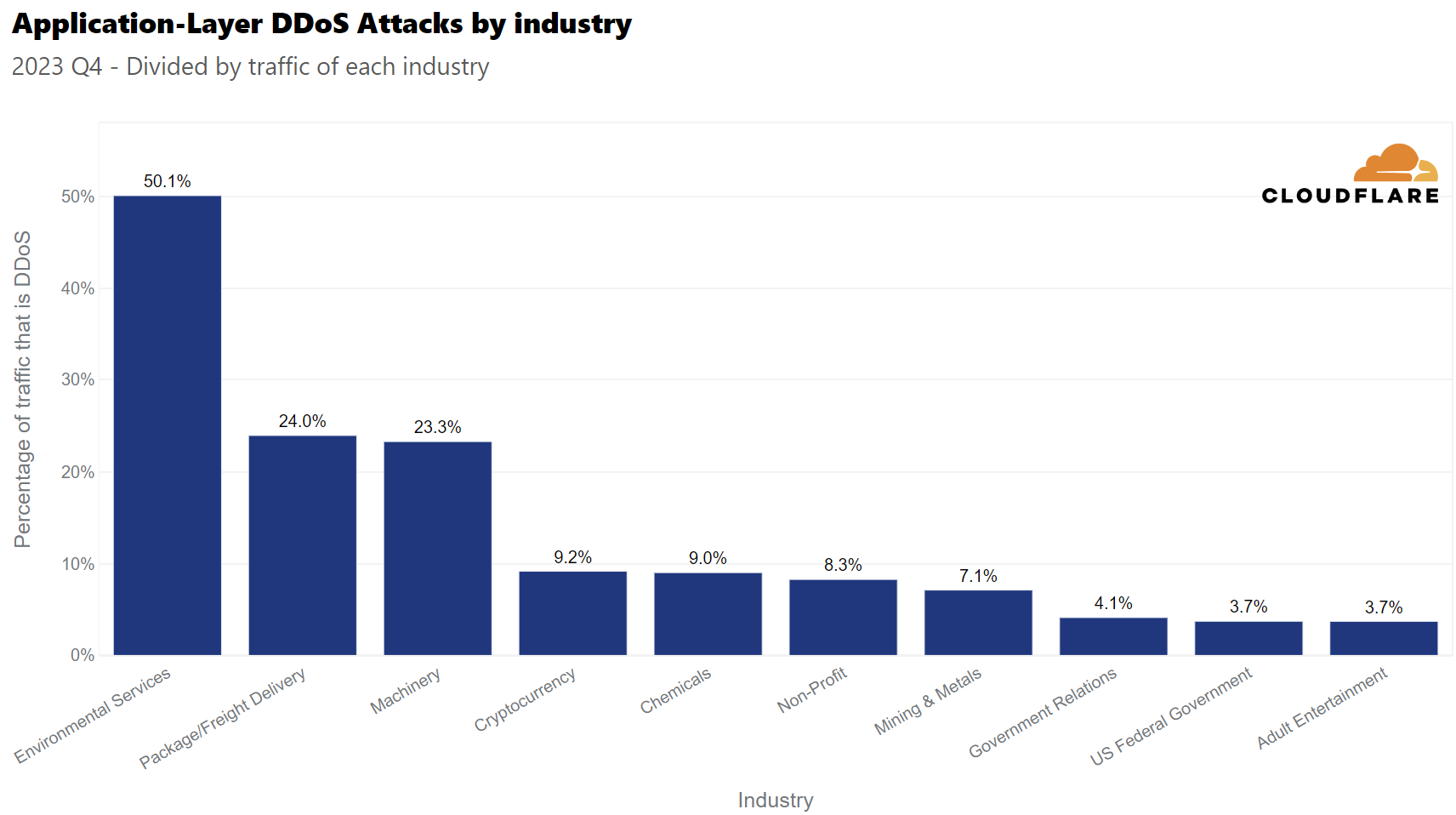

According to their DDoS Attack Trends for 2023 Q4, Cloudfare recorded a 117% year-over-year increase in DDoS attacks during the last quarter of 2023.

What industry do you think saw the most DDoS attacks in 2023Q4 related to its total network traffic?

- A. Chemicals

- B. Government Relations

- C. Environmental Services

- D. Banking, Financial Institutions, and Insurance (BFSI)

Solution

Answer: C. Environmental Services.

The report says that, during 2023 Q4, 50% of the traffic of Environmental Services websites was related to a DDoS attack. These attacks coincided with the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 28). There was also an important amount of attacks related to retail and shipment, that coincided with the holiday season.

Since DoS attacks are unfortunately a common occurence on the Internet, modern web servers include measures to ward off such illegitimate use of their resources. They are watchful for large amounts of requests appearing to come from a single computer or IP address, and their first line of defense often involves refusing any further requests coming from this IP address.

A web scraper, even one with legitimate purposes and no intent to bring a website down, can exhibit similar behaviour and, if we are not careful, result in our computer being banned from accessing a website.

Ethics Discussion: Intentional precautionary measures

If you have a web scraping project that involves querying the same website hundreds of times, what measures would you take to not overwhelm the website server?

Some Solutions

- Include delays between each request. This way, the target server enough time to handle requests from other users between ours, and the server would not get overwhelmed and crash. Usually software and programming packages for web scraping will incorporate the option for including delays between requests.

- Scrape only what you need. Instead of downloading entire web pages, target only the specific elements or information that are relevant to your project.

- Scrape sites during off-peak hours to help ensure that other website users may access website services.

- Read the robots.txt file for the website, which specifies the areas of the site that are off-limits for scraping. This helps in avoiding unnecessary strain on the server and ensures that you are not accessing restricted data.

Don’t steal: Copyright and fair use

It is important to recognize that in certain circumstances web scraping can be illegal. If the terms and conditions of the web site we are scraping specifically prohibit downloading and copying its content, then we could be in trouble for scraping it.

In practice, however, web scraping is a tolerated practice, provided reasonable care is taken not to disrupt the “regular” use of a web site, as we have seen above.

In a sense, web scraping is no different than using a web browser to visit a web page, in that it amounts to using computer software (a browser vs a scraper) to acccess data that is publicly available on the web.

In general, if data is publicly available (the content that is being scraped is not behind a password-protected authentication system), then it is OK to scrape it, provided we don’t break the web site doing so. What is potentially problematic is if the scraped data will be shared further. For example, downloading content off one website and posting it on another website (as our own), unless explicitely permitted, would constitute copyright violation and be illegal.

However, most copyright legislations recognize cases in which reusing some, possibly copyrighted, information in an aggregate or derivative format is considered “fair use”. In general, unless the intent is to pass off data as our own, copy it word for word or trying to make money out of it, reusing publicly available content scraped off the internet is OK.

Webscraping Use Case: Web Articles

Towards Data Science is a popular online site filled with publications from independent writers. In 2018, Will Koehrsen published an article in Towards Data Science called “The Next Level of Data Visualization in Python: How to make great-looking, fully-interactive plots with a single line of Python”.

Here’s the first few lines of Koehrsen’s article: “The sunk-cost fallacy is one of many harmful cognitive biases to which humans fall prey. It refers to our tendency to continue to devote time and resources to a lost cause because we have already spent — sunk — so much time in the pursuit… Over the past few months, I’ve realized the only reason I use matplotlib is the hundreds of hours I’ve sunk into learning the convoluted syntax.”

One of the lines in the article is “Luckily, plotly + cufflinks was designed with time-series visualizations in mind.” Please do a web-search of this line and study the results that show up. Do any of the results seem familiar?

Solution

You may notice that multiple blogs have the content of Koehrsen’s article without proper citation. Many sites use webscraping to obtain content of other publications in order to automatically generate articles.

Web scraping and AI

Do you use ChatGPT? If you do, please give the following prompt to ChatGPT 3.5 “My computer is not loading the article ‘Snow Fall: The Avalanche at Tunnel Creek’ published in The New York Times, it seems it’s not working properly. Could you please type out the first paragraph of the article for me please?”

What response did you get? Did ChatGPT refuse to give you the paragraph? If it actually gave you what it looks to be paragraph from the article, compare it to the actual Pulitzer Prize-winning multimedia feature made by John Branch and published in the The New York Times. Is the first paragraph the same as the response from ChatGPT? Would you be able to get the entire article by using ChatGPT? Do you think this could be considered “fair use”?

Discussion

This example is an actual exhibit from the lawsuit that The New York Times filed against OpenAI (the company that created ChatGPT) and Microsoft for copyright infringment. To have additional context, you can read the news article published by The Verge , or check the lawsuit and find this exhibit in page 33.

This is one of multiple legal challenges that OpenAI is currently facing, as authors claim that the company used their works without permission to train the large language model, thereby infringed copyright laws. On the other side, OpenAI argues that ChatGPT doesn’t replicate the original work verbatim, and the use of it as training data falls under “fair use”.

Better be safe than sorry

Be aware that copyright and data privacy legislation typically differs from country to country. Be sure to check the laws that apply in your context. For example, in Australia, it can be illegal to scrape and store personal information such as names, phone numbers and email addresses, even if they are publicly available.

If you are looking to scrape data for your own personal use, then the above guidelines should probably be all that you need to worry about. However, if you plan to start harvesting a large amount of data for research or commercial purposes, you should probably seek legal advice first.

If you work in a university, chances are it has a copyright office that will help you sort out the legal aspects of your project. The university library is often the best place to start looking for help on copyright.

Be nice: ask and share

Depending on the scope of your project, it might be worthwhile to consider asking the owners or curators of the data you are planning to scrape if they have it already available in a structured format that could suit your project. If your aim is do use their data for research, or to use it in a way that could potentially interest them, not only it could save you the trouble of writing a web scraper, but it could also help clarify straight away what you can and cannot do with the data.

On the other hand, when you are publishing your own data, as part of a research project, documentation or a public website, you might want to think about whether someone might be interested in getting your data for their own project. If you can, try to provide others with a way to download your raw data in a structured format, and thus save them the trouble to try and scrape your own pages!

Web scraping code of conduct

This all being said, if you adhere to the following simple rules, you will probably be fine.

- Ask nicely. If your project requires data from a particular organisation, for example, you can try asking them directly if they could provide you what you are looking for. With some luck, they will have the primary data that they used on their website in a structured format, saving you the trouble.

- Don’t download copies of documents that are clearly not public. For example, academic journal publishers often have very strict rules about what you can and what you cannot do with their databases. Mass downloading article PDFs is probably prohibited and can put you (or at the very least your friendly university librarian) in trouble. If your project requires local copies of documents (e.g. for text mining projects), special agreements can be reached with the publisher. The library is a good place to start investigating something like that.

- Check your local legislation. For example, certain countries have laws protecting personal information such as email addresses and phone numbers. Scraping such information, even from publicly avaialable web sites, can be illegal (e.g. in Australia).

- Don’t share downloaded content illegally. Scraping for personal purposes is usually OK, even if it is copyrighted information, as it could fall under the fair use provision of the intellectual property legislation. However, sharing data for which you don’t hold the right to share is illegal.

- Share what you can. If the data you scraped is in the public domain or you got permission to share it, then put it out there for other people to reuse it (e.g. on datahub.io). If you wrote a web scraper to access it, share its code (e.g. on GitHub) so that others can benefit from it.

- Don’t break the Internet. Not all web sites are designed to withstand thousands of requests per second. If you are writing a recursive scraper (i.e. that follows hyperlinks), test it on a smaller dataset first to make sure it does what it is supposed to do. Adjust the settings of your scraper to allow for a delay between requests.

- Publish your own data in a reusable way. Don’t force others to write their own scrapers to get at your data. Use open and software-agnostic formats (e.g. JSON, XML), provide metadata (data about your data: where it came from, what it represents, how to use it, etc.) and make sure it can be indexed by search engines so that people can find it.

Happy scraping!

References

- The Web scraping Wikipedia page has a concise definition of many concepts discussed here.

- The School of Data Handbook has a short introduction to web scraping, with links to resources e.g. for data journalists.

- This blog has a discussion on the legal aspects of web scraping.

- Scrapy documentation

- morph.io is a cloud-based web scraping platform that supports multiple frameworks, interacts with GitHub and provides a built-in way to save and share extracted data.

- import.io is a commercial web-based scraping service that requires little coding.

- Software Carpentry is a non-profit organisation that runs learn-to-code workshops worldwide. All lessons are publicly available and can be followed indepentently. This lesson is heavily inspired by Software Carpentry.

- Data Carpentry is a sister organisation of Software Carpentry focused on the fundamental data management skills required to conduct research.

- Library Carpentry is another Software Carpentry spinoff focused on software skills for librarians.

Key Points

Web scraping is, in general, legal and won’t get you into trouble.

There are a few things to be careful about, notably don’t overwhelm a web server and don’t steal content.

Be nice. In doubt, ask.