Dynamic websites

Last updated on 2024-11-04 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 35 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What are the differences between static and dynamic websites?

- Why is it important to understand these differences when doing web scraping?

- How can I start my own web scraping project?

Objectives

- Use the

Seleniumpackage to scrape dynamic websites. - Identify the elements of interest using the browser’s “Inspect” tool.

- Understand the usual pipeline of a web scraping project.

You see it but the HTML doesn’t have it!

Visit the following webpage created by Hartley Brody for the purpose of learning and practicing web scraping: https://www.scrapethissite.com/pages/ajax-javascript/ (read first the terms of use). Select “2015” to see that year’s Oscar winning films. Now look at the HTML behind it as we’ve learned, using the “View page source” tool on your browser or in Python using the requests and BeautifulSoup packages. Can you find in any place of the HTML the best picture winner “Spotlight”? Can you find any other of the movies or the data from the table? If you can’t, how could you scrape this page?

When you explore a page like this, you’ll notice that the movie data,

including the title “Spotlight,” isn’t actually in the initial HTML

source. This is because the website uses JavaScript to load the

information dynamically. JavaScript is a programming language that runs

in your browser, allowing websites to fetch, process, and display

content on the fly, often based on user actions like clicking a button.

When you select “2015”, the browser executes JavaScript (called by one

of the <script> elements you see in the HTML) to

retrieve the relevant movie information from the web server and build a

new HTML document with actual information in the table. This makes the

page feel more interactive, but it also means the initial HTML you see

doesn’t contain the movie data itself.

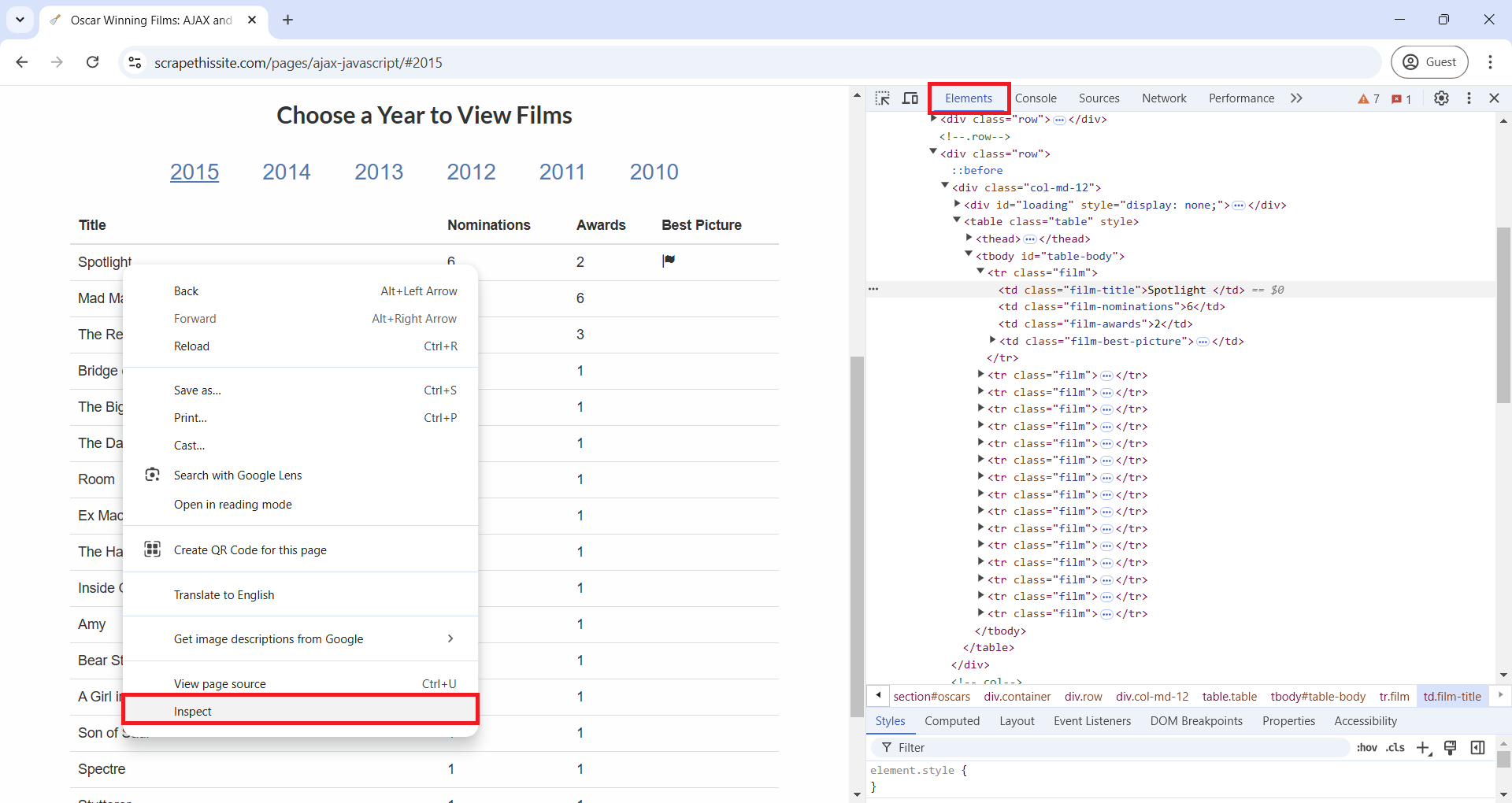

Let’s explore a new way to view HTML elements in your browser to better understand the differences in an HTML document before and after JavaScript is executed. On the Oscar winners page you just visited, right-click (or Control key + Click on Mac) and select “Inspect” from the pop-up menu, as shown in the image below. This opens DevTools on the side of your browser, offering a range of features for inspecting, debugging, and analyzing web pages in real-time. For this workshop, however, we’ll focus on just the “Elements” tab. In the “Elements” tab, you’ll see an HTML document that actually includes the table element, unlike what you saw in “View Page Source”. This difference is because “View Page Source” displays the original HTML, before any JavaScript is run, while “Inspect” reveals the HTML as it appears after JavaScript has executed.

As the requests package retrieves the source HTML, we

need a different approach to scrape these types of websites. For this,

we will use the Selenium package. But don’t forget about

the “Inspect” tool we just learned, it will be handy when scraping.

Using Selenium to scrape dynamic websites

Selenium is an open source project for web browser automation. It will be useful for our scraping tasks as it will act as a real user interacting with a webpage in a browser. This way, Selenium will render pages in a browser environment, allowing JavaScript to load dynamic content, and therefore giving us access to the website HTML after JavaScript has executed. Additionally, this package simulates real user interactions like filling in text boxes, clicking, scrolling, or selecting drop-down menus, which will be useful when we scrape dynamic websites.

To use it, we’ll load “webdriver” and “By” from the

selenium package. webdriver open or simulate a web browser,

interacting with it based on the instructions we give. By will allow us

to specify how we will select a given element in the HTML, by tag (using

“By.TAG_NAME”) or by attributes like class (“By.CLASS_NAME”), id

(“By.ID”), or name (“By.NAME”). We will also load the other packages we

used in the previous episode.

PYTHON

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import pandas as pd

from time import sleep

from selenium import webdriver

from selenium.webdriver.common.by import BySelenium can simulate multiple multiple browsers like Chrome, Firefox, Safari, etc. For now, we’ll use Chrome. When you run the following line of code, you’ll notice that a Google Chrome window opens up. Don’t close it, as this is how Selenium interacts with the browser. Later we’ll see how to do headless browser interactions, headless meaning that browser interactions will happen in the background, without opening a new browser window or user interface.

Now, to tell the browser to visit our Oscar winners page, use the

.get() method on the driver object we just

created.

How can we direct Selenium to click the text “2015” for the table of

that year tho show up? First, we need to find that element, in a similar

way to how we find elements with BeautifulSoup. Just like we used

.find() in BeautifulSoup to find the first element that

matched the specified criteria, in Selenium we have

.find_element(). Likewise, as we used

.find_all() in BeautifulSoup to return a list of all

coincidences for our search criteria, we can use

.find_elements() in Selenium. But the syntax of how we

specify the search paramenters will be a little different.

If we wanted to search a table element that has the

<table> tag, we would run

driver.find_element(by=By.TAG_NAME, value="table"). If we

wanted to search an element with a specific value in the “class”

attribute, for example an element like

<tr class="film"> we would run

driver.find_element(by=By.CLASS_NAME, value="film"). To

know what element we need to click to open “2015” table of Oscar winners

we can use the “Inspect” tool (remember you can do this in Google Chrome

by pointing your mouse over the “2015” value, make a right-click, and

select “Inspect” from the pop-up menu). In the DevTools window, you’ll

see element

<a href="#" class="year-link" id="2015">2015</a>.

As the ID attribute is unique for only one element in the HTML, we can

directly select the element by this attribute using the code you’ll find

after the following image.

We’ve located the hyperlink element we want to click to get the table

for that year, and on that element we will use the .click()

method to interact with it. As the table takes a couple of seconds to

load, we will also use the sleep() function from the “time”

module to wait will the JavaScript runs and the table loads. Then, we

use driver.page_source for Selenium to get the HTML

document from the website, and we store it in a variable called

html_2015. Finally, we close the web browser that Selenium

was using with driver.quit().

Importantly, the HTML document we stored in html_2015

is the HTML after the dynamic content loaded, so it

will contain the table values for 2015 that weren’t there originally and

that we wouldn’t be able to see if we had used the requests

package instead.

We could continue using Selenium and its .find_element()

and .find_elements() methods to to extract our data of

interest. But instead, we will use BeautifulSoup to parse the HTML and

find elements, as we already have some practice using it. If we search

for the first element with class attribute equal to “film-title” and

return the text inside it, we see that this HTML has the “Spotlight”

movie.

PYTHON

<tr class="film">

<td class="film-title">

Spotlight

</td>

<td class="film-nominations">

6

</td>

<td class="film-awards">

2

</td>

<td class="film-best-picture">

<i class="glyphicon glyphicon-flag">

</i>

</td>

</tr>The following code repeats the process of clicking and loading the

2015 data, but now using “headless” mode (i.e. without opening a browser

window). Then, it extracts data from the table one column at a time,

taking advantage that each column has a unique class attribute that

identifies it. Instead of using for loops to extract data from each

element that .find_all() finds, we use list comprehensions.

You can learn more about them reading Python’s

documentation for list comprehensions, or with this Programiz

short tutorial.

PYTHON

# Create the Selenium webdriver and make it headless

options = ChromeOptions()

options.add_argument("--headless=new")

driver = webdriver.Chrome(options=options)

# Load the website. Find and click 2015. Get post JavaScript execution HTML. Close webdriver

driver.get("https://www.scrapethissite.com/pages/ajax-javascript/")

button_2015 = driver.find_element(by=By.ID, value="2015")

button_2015.click()

sleep(3)

html_2015 = driver.page_source

driver.quit()

# Parse HTML using BeautifulSoup and extract each column as a list of values ising list comprehensions

soup = BeautifulSoup(html_2015, 'html.parser')

titles_lc = [elem.get_text() for elem in soup.find_all(class_="film-title")]

nominations_lc = [elem.get_text() for elem in soup.find_all(class_="film-nominations")]

awards_lc = [elem.get_text() for elem in soup.find_all(class_="film-awards")]

# For the best picture column, we can't use .get_text() as there is no text

# Rather, we want to see if there is an <i> tag

best_picture_lc = ["Yes" if elem.find("i") == None else "No" for elem in soup.find_all(class_="film-best-picture")]

# Create a dataframe based on the previous lists

movies_2015 = pd.DataFrame(

{'titles': titles_lc, 'nominations': nominations_lc, 'awards': awards_lc, 'best_picture': best_picture_lc}

)Challenge

Based on what we’ve learned in this episode, write code for getting the data of all the years from 2010 to 2015 of Hartley Brody’s website with information of Oscar Winning Films. Hint: You’ll use the same code, but add loop through each year.

Besides adding a loop for each year, the following solution is refactoring the code by creating two functions: one that finds and clicks a year returning the html after the data shows up, and another that gets the html and parses it to extract the data and create a dataframe.

So you can see the process of how Selenium opens the browser and clicks the years, we are not adding the “headless” option.

PYTHON

# Function to search year hyperlink and click it

def findyear_click_gethtml(year):

button = driver.find_element(by=By.ID, value=year)

button.click()

sleep(3)

html = driver.page_source

return html

# Function to parse html, extract table data, and assign year column

def parsehtml_extractdata(html, year):

soup = BeautifulSoup(html, 'html.parser')

titles_lc = [elem.get_text() for elem in soup.find_all(class_="film-title")]

nominations_lc = [elem.get_text() for elem in soup.find_all(class_="film-nominations")]

awards_lc = [elem.get_text() for elem in soup.find_all(class_="film-awards")]

best_picture_lc = ["No" if elem.find("i") == None else "Yes" for elem in soup.find_all(class_="film-best-picture")]

movies_df = pd.DataFrame(

{'titles': titles_lc, 'nominations': nominations_lc, 'awards': awards_lc, 'best_picture': best_picture_lc, 'year': year}

)

return movies_df

# Open Selenium webdriver and go to the page

driver = webdriver.Chrome()

driver.get("https://www.scrapethissite.com/pages/ajax-javascript/")

# Create empty dataframe where we will append/concatenate the dataframes we get for each year

result_df = pd.DataFrame()

for year in ["2010", "2011", "2012", "2013", "2014", "2015"]:

html_year = findyear_click_gethtml(year)

df_year = parsehtml_extractdata(html_year, year)

result_df = pd.concat([result_df, df_year])

# Close the browser that Selenium opened

driver.quit()Challenge

If you are tired of scraping table data like we’ve been doing for the last two episodes, here is another dynamic website exercise where you can practice what you’ve learned. Go to this product page created by scrapingcourse.com and extract all product names and prices, and also the hyperlink that each product card has to a detailed view page.

When you complete that, and if you are up to an additional challenge, scrape from the detailed view page of each product its SKU, Category and Description.

To identify what elements containt the data you need, you should use

the “Inspect” tool in your browser. The following image is a screenshot

of the website. In there we can see that each product card is a

<div> element with multiple attributes that we can

use to narrow down our search to the specific elements we want. For

example, we would use 'data-testid'='product-item'. After

we find all divs that satisfy that condition, we can extract

from each the hyperlink, the name, and the price. The hyperlink is the

‘href’ attribute of the <a> tag. The name and price

are inside <span> tags, and we could use multiple

attributes to get each of them. In the following code, we will use

'class'='product-name' to get the name and

'data-content'='product-price' to get the price.

PYTHON

# Open Selenium webdriver in headless mode and go to the desired page

options = webdriver.ChromeOptions()

options.add_argument("--headless=new")

driver = webdriver.Chrome(options=options)

driver.get("https://www.scrapingcourse.com/javascript-rendering")

# As we don't have to click anything, just wait for the JavaScript to load, we can get the HTML right away

sleep(3)

html = driver.page_source

# Parste the HTML

soup = BeautifulSoup(html, 'html.parser')

# Find all <div> elements that have a 'data-testid' attribute with the value of 'product-item'

divs = soup.find_all("div", attrs = {'data-testid': 'product-item'})

# Loop through the <div> elements we found, and for each get the href,

# the name (inside a <span> element with attribute class="product-name")

# and the price (inside a <span> element with attribute data-content="product-price"

list_of_dicts = []

for div in divs:

# Create a dictionary to store the data we want for each product

item_dict = {

'link': div.find('a')['href'],

'name': div.find('span', attrs = {'class': 'product-name'}).get_text(),

'price': div.find('span', attrs = {'data-content': 'product-price'}).get_text()

}

list_of_dicts.append(item_dict)

all_products = pd.DataFrame(list_of_dicts)We could arrive to the same result if we replace the for loop with list comprehensions. So here is another possible solution with that approach.

PYTHON

links = [elem['href'] for elem in soup.find_all('a', attrs = {'class': 'product-link'})]

names = [elem.get_text() for elem in soup.find_all('span', attrs = {'class': 'product-name'})]

prices = [elem.get_text() for elem in soup.find_all('span', attrs = {'data-content': 'product-price'})]

all_products_v2 = pd.DataFrame(

{'link': links, 'name': names, 'price': prices}

)The scraping pipeline

By now, you’ve learned about the core tools for web scraping: requests, BeautifulSoup, and Selenium. These three tools form a versatile pipeline for almost any web scraping task. When starting a new scraping project, there are several important steps to follow that will help ensure you capture the data you need.

The first step is understanding the website structure. Every website is different and structures data in its own particular way. Spend some time exploring the site and identifying the HTML elements that contain the information you want. Next, determine if the content is static or dynamic. Static content can be directly accessed from the HTML source code using requests and BeautifulSoup, while dynamic content often requires Selenium to load JavaScript on the page before BeautifulSoup can parse it.

Once you know how the website presents its data, start

building your pipeline. If the content is static, make a

requests call to get the HTML document, and use

BeautifulSoup to locate and extract the necessary elements.

If the content is dynamic, use Selenium to load the page

fully, perform any interactions (like clicking or scrolling), and then

pass the rendered HTML to BeautifulSoup for parsing and

extracing the necessary elements. Finally, format and store the

data in a structured way that’s useful for your specific

project and that makes it easy to analyse later.

This scraping pipeline helps break down complex scraping tasks into manageable steps and allows you to adapt the tools based on the website’s unique features. With practice, you’ll be able to efficiently combine these tools to extract valuable data from almost any website.

Key Points

- Dynamic websites load content using JavaScript, which isn’t present in the initial or source HTML. It’s important to distinguish between static and dynamic content when planning your scraping approach.

- The

Seleniumpackage and itswebdrivermodule simulate a real user interacting with a browser, allowing it to execute JavaScript and clicking, scrolling or filling in text boxes. - Here are the commandand we learned when we use

Selenium:-

webdriver.Chrome()# Start the Google Chrome browser simulator -

.get("website_url")# Go to a given website -

.find_element(by, value)and.find_elements(by, value)# Get a given element -

.click()# Click the element selected -

.page_source# Get the HTML after JavaScript has executed, which can later be parsed with BeautifulSoup -

.quit()# Close the browser simulator

-

- The browser’s “Inspect” tool allows users to view the HTML document after dynamic content has loaded, revealing elements added by JavaScript. This tool helps identify the specific elements you are interested in scraping.

- A typical scraping pipeline involves understanding the website’s structure, determining content type (static or dynamic), using the appropriate tools (requests and BeautifulSoup for static, Selenium and BeautifulSoup for dynamic), and structuring the scraped data for analysis.