Counting and extracting with the shell

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How can I count data?

How can I find data within files?

How can I combine existing commands to do new things?

Objectives

Demonstrate counting lines, words, and characters with the shell command wc and appropriate flags

Use strings to mine files and extract matched lines with the shell

Create complex single line commands by combining shell commands and regular expressions to mine files

Redirect a command’s output to a file.

Process a file instead of keyboard input using redirection.

Construct command pipelines with two or more stages.

Explain Unix’s ‘small pieces, loosely joined’ philosophy.

Counting and mining data

Now that you know how to navigate the shell, we will move onto learning how to count and mine data using a few of the standard shell commands. While these commands are unlikely to revolutionise your work by themselves, they’re very versatile and will add to your foundation for working in the shell and for learning to code. The commands also replicate the sorts of uses library users might make of library data.

Counting and sorting

We will begin by counting the contents of files using the Unix shell. We can use the Unix shell to quickly generate counts from across files, something that is tricky to achieve using the graphical user interfaces of standard office suites.

Let’s start by navigating to the directory that contains our data using the

cd command:

$ cd shell-lesson

Remember, if at any time you are not sure where you are in your directory structure,

use the pwd command to find out:

$ pwd

/Users/your.username/Desktop/shell-lesson/data

And let’s just check what files are in the directory and how large they

are with ls -lhS:

$ ls -lhs

total 6.6M

384K -rw-r--r-- 1 your.username 1049089 384K Mar 12 16:25 000003160_01_text.json

584K -rw-r--r-- 1 your.username 583K Mar 12 16:25 33504-0.txt

600K -rw-r--r-- 1 your.username 598K Mar 12 16:25 829-0.txt

0 drwxr-xr-x 1 your.username 1049089 0 Mar 18 13:23 airphotodata/

4.0K drwxr-xr-x 1 your.username 1049089 0 Mar 18 13:23 desktrackers/

20K -rw-r--r-- 1 your.username 1049089 19K Mar 12 16:25 diary.html

1.1M -rw-r--r-- 1 your.username 1049089 1.1M Mar 12 16:25 pg514.txt

4.0M -rw-r--r-- 1 your.username 1049089 4.0M Mar 16 15:40 shell-lesson.zip

0 drwxr-xr-x 1 your.username 1049089 0 Mar 18 13:35 waitz/

In this episode we’ll focus on the datasets in the desktracker

directory, that contains four .csv Desktracker files.

CSV and TSV Files

CSV (Comma-separated values) is a common plain text format for storing tabular data, where each record occupies one line and the values are separated by commas. TSV (Tab-separated values) is just the same except that values are separated by tabs rather than commas. Confusingly, CSV is sometimes used to refer to both CSV, TSV and variations of them. The simplicity of the formats make them great for exchange and archival. They are not bound to a specific program (unlike Excel files, say, there is no

CSVprogram, just lots and lots of programs that support the format, including Excel by the way.), and you wouldn’t have any problems opening a 40 year old file today if you came across one.

First, let’s have a look at the the 2016 file, using the tools we learned in Reading files:

$ cat Desk_Tracker.csv

Like 829-0.txt before, the whole dataset cascades by and can’t really make any

sense of that amount of text. To cancel this on-going concatenation, or indeed any

process in the Unix shell, press Ctrl+C.

In most data files a quick glimpse of the first few lines already tells us a lot about the structure of the dataset, for example the table/column headers:

$ head -n 3 Desk_Tracker.csv

response_set_id,parent_response_set_id,date_time,page,user,branch,desk,library,Contact

Type,Contact Type (text),Question Type,Question Type

(text),Directional Informational Type,Directional

Informational Type (text),Time Spent in

minutes,Comment,Reference Research Type,Reference

Research Type (text),Number of Participants,Instructor,Type

of Event,Type of Event (text),Date & Time,Unit Area Name,Unit

Area Name (text),How many patrons were in the Art &

Architecture Collection,Ref Question Type,Ref Question Type

(text),Directional Informational Type,Directional

Informational Type (text),Comments,Reference Research

Type,Reference Research Type (text),Directional

Informational Type 2,Directional Informational Type 2

(text),Directional Informational Type 3,Directional

Informational Type 3 (text),Directional Informational Type

4,Directional Informational Type 4 (text),Directional

Informational Type 5,Directional Informational Type 5

(text),Directional Informational Type 6,Directional

Informational Type 6 (text),Directional Informational Type

7,Directional Informational Type 7 (text),Directional

Informational Type 8,Directional Informational Type 8

(text),Directional Informational Type 9,Directional

Informational Type 9 (text),Directional Informational Type

10,Directional Informational Type 10 (text),Directional

Informational Type 11,Directional Informational Type 11

(text),Directional Informational Type 12,Directional

Informational Type 12 (text),Directional Informational Type

13,Directional Informational Type 13 (text),Reference

Research Type 2,Reference Research Type 2 (text),Reference

Research Type 3,Reference Research Type 3 (text),Reference

Research Type 4,Reference Research Type 4 (text),Question

Type 2,Question Type 2 (text),Reference Research Type

2,Reference Research Type 2 (text),Reference Research

Type 3,Reference Research Type 3 (text),Type of

Question,Type of Question (text),Time Spent on Question,Time

Spent on Question (text),Brief Description of

Question,Reference Research Type 4,Reference Research

Type 4 (text),Date Time,Gate Count,Reference Research

Type,Reference Research Type (text),Question Type

required,Question Type required (text)

"9898","","2016-01-04 08:00:00","Desk

Statistics","RefBuddy","Reference Services","Information

Desk","University of California, Santa Barbara","In

Person","","Directional /

Informational","","Directions/Locations (where to

find)","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","",""

"9899","","2016-01-04 08:00:00","Desk

Statistics","RefBuddy","Reference Services","Information

Desk","University of California, Santa Barbara","In

Person","","Directional /

Informational","","Directions/Locations (where to

find)","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","","",""

"","","",""

In the header, we can see the common metadata fields of Desktracker:

user, Contact Type, `library’.

Next, let’s learn about a basic data analysis tool:

wc is the “word count” command: it counts the number of lines, words, and bytes.

Since we love the wildcard operator, let’s run the command

wc *.csv to get counts for all the .csv files in the Desktrackers

directory.

(it takes a little time to complete):

$ wc *.csv

122995 2171893 54797588 Desk_Tracker.csv

43842 757941 18654589 Desk_Tracker_2016.csv

31456 565013 12271344 Desk_Tracker_2017.csv

27274 491149 9833562 Desk_Tracker_2018.csv

20426 358164 6947675 Desk_Tracker_2019.csv

245993 4344160 102504758 total

The first three columns contains the number of lines, words and bytes.

If we only have a handful of files to compare, it might be faster or more convenient to just check with Microsoft Excel, OpenRefine or your favourite text editor, but when we have tens, hundreds or thousands of documents, the Unix shell has a clear speed advantage. The real power of the shell comes from being able to combine commands and automate tasks, though. We will touch upon this slightly.

For now, we’ll see how we can build a simple pipeline to find the shortest file

in terms of number of lines. We start by adding the -l flag (this looks

confusing in the shell, but this is a lower-case letter L, not the number one) to get

only the number of lines, not the number of words and bytes:

$ wc -l *.csv

122995 Desk_Tracker.csv

43842 Desk_Tracker_2016.csv

31456 Desk_Tracker_2017.csv

27274 Desk_Tracker_2018.csv

20426 Desk_Tracker_2019.csv

245993 total

The wc command itself doesn’t have a flag to sort the output, but as we’ll

see, we can combine three different shell commands to get what we want.

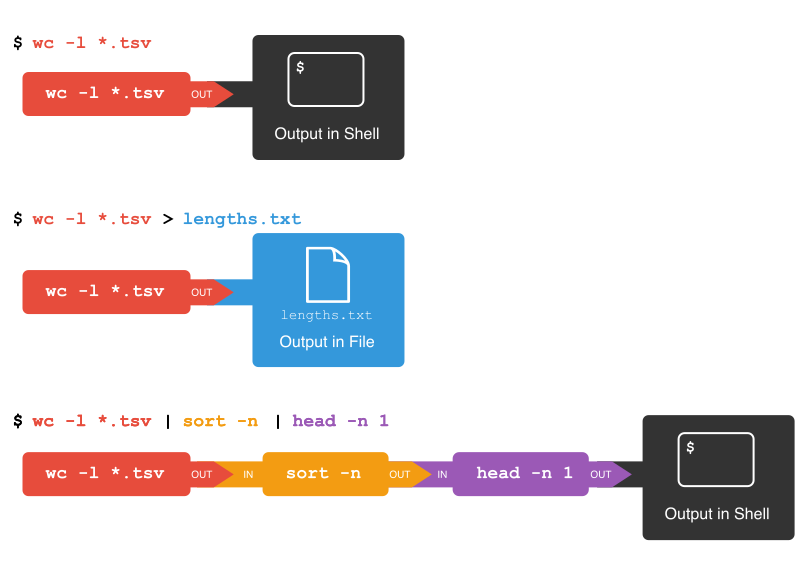

First, we have the wc -l *.csv command. We will save the output from

this command in a new file. To do that, we redirect the output from the

command to a file using the ‘greater than’ sign (>), like so:

$ wc -l *.csv > lengths.txt

There’s no output now since the output went into the file lengths.txt, but

we can check that the output indeed ended up in the file using cat or less

(or Notepad or any text editor).

$ cat lengths.txt

122995 Desk_Tracker.csv

43842 Desk_Tracker_2016.csv

31456 Desk_Tracker_2017.csv

27274 Desk_Tracker_2018.csv

20426 Desk_Tracker_2019.csv

245993 total

Next, there is the sort command. We’ll use the -n flag to specify that we

want numerical sorting, not lexical sorting, we output the results into

yet another file, and we use cat to check the results:

$ sort -n lengths.txt > sorted-lengths.txt

$ cat sorted-lengths.txt

20426 Desk_Tracker_2019.csv

27274 Desk_Tracker_2018.csv

31456 Desk_Tracker_2017.csv

43842 Desk_Tracker_2016.csv

122995 Desk_Tracker.csv

Writing to files

The

datecommand outputs the current date and time. Can you write the current date and time to a new file calledlogfile.txt? Then check the contents of the file.Solution

Appending to a file

While

>writes to a file,>>appends something to a file. Try to append the current date and time to the filelogfile.txt?Solution

Finally we have our old friend head, that we can use to get the first

line of the sorted-lengths.txt:

(Earlier, we had the issue of is this a lower case L or a number one.

Here, its the number 1 because the ‘-n’ is for sorting lines, and we want the number)

$ head -n 1 sorted-lengths.txt

20426 Desk_Tracker_2019.csv

But we’re really just interested in the end result, not the intermediate

results now stored in lengths.txt and sorted-lengths.txt. What if we could

send the results from the first command (wc -l *.csv) directly to the

next

command (sort -n) and then the output from that command to head -n 1?

Luckily we can, using a concept called pipes. On the command line, you make a

pipe with the vertical bar character |. Let’s try with one pipe first:

$ wc -l *.csv | sort -n

20426 Desk_Tracker_2019.csv

27274 Desk_Tracker_2018.csv

31456 Desk_Tracker_2017.csv

43842 Desk_Tracker_2016.csv

122995 Desk_Tracker.csv

245993 total

Notice that this is exactly the same output that ended up in our sorted-lengths.txt

earlier. Let’s add another pipe:

$ wc -l *.csv | sort -n | head -n 1

20426 Desk_Tracker_2019.csv

It can take some time to fully grasp pipes and use them efficiently, but it’s a very powerful concept that you will find not only in the shell, but also in most programming languages.

Pipes and Filters

This simple idea is why Unix has been so successful. Instead of creating enormous programs that try to do many different things, Unix programmers focus on creating lots of simple tools that each do one job well, and that work well with each other. This programming model is called “pipes and filters”. We’ve already seen pipes; a filter is a program like

wcorsortthat transforms a stream of input into a stream of output. Almost all of the standard Unix tools can work this way: unless told to do otherwise, they read from standard input, do something with what they’ve read, and write to standard output.The key is that any program that reads lines of text from standard input and writes lines of text to standard output can be combined with every other program that behaves this way as well. You can and should write your programs this way so that you and other people can put those programs into pipes to multiply their power.

Adding another pipe

We have our

wc -l *.csv | sort -n | head -n 1pipeline. What would happen if you piped this intocat? Try it!Solution

Extracting data from our dataset

When you receive data it will often contain more columns or variables than you need for your work. If you want to select

only the columns you need for your analysis, you can use the cut command to do so. cut is a tool for extracting sections

from a file.

For instance, say we want to retain only the response_set_id, date_time, Question Type, and Contact

Type columns from our article data. With cut we’d:

cut -f1,3,10,12 -d "," Desk_Tracker_2017.csv | headresponse_set_id,date_time,Contact Type (text),Question Type (text) "51530", "2017-01-03 08:02:32", "Personal Email", "Reference / Research Assistance" "51800", "2017-01-09 14:57:27", "In Person", "Reference / Research Assistance" "51801", "2017-01-09 14:57:47", "In Person", "Directional / Informational" "52089", "2017-01-11 14:17:19", "In Person", "Reference / Research Assistance" "52209", "2017-01-12 15:23:41", "In Person", "Directional / Informational" "52240", "2017-01-12 18:51:06". "In Person", "Reference / Research Assistance" "52335", "2017-01-13 15:06:25", "Personal Email", "Reference / Research Assistance" "52336", "2017-01-13 15:07:19", "In Person", "Reference / Research Assistance" "52337", "2017-01-13 15:07:33", "Personal Email", "Reference / Research Assistance"Above we used

cutand the-fflag to indicate which columns we want to retain.cutworks on tab delimited files by default. We can use the flag-dto change this to a comma or some other delimeter. If you are unsure of your column position and the file has headers on the first line, we can usehead -n 1 <filename>to print those out.Now your turn

Select the columns

response_time_id,date_time,Contact Type,Question Typeand direct the output into a new file using>as described in the previous episode. You can name it something likeDesk_Tracker_2016_simp.csv.Solution

Count, sort and print

A ‘faded example’ is a partially solved problem. Let’s build on what we know and fill in the blanks.

To count the total lines in every

csvfile, sort the results and then print the first line of the file we use the following:wc -l *.csv | sort -n | head -n 1Now let’s change the scenario. Let’s say we have a whole collection of files, and we want to know the 10 files that contain the most words. Fill in the blanks below to count the words for each file, put them into order, and then make an output of the 10 files with the most words (Hint: The sort command sorts in ascending order by default).

__ -w *.csv | sort __ | ____Solution

Counting number of files

Let’s make a different pipeline. You want to find out how many files and directories there are in the current directory. Try to see if you can pipe the output from

lsintowcto find the answer, or something close to the answer.Solution

Counting the number of words

Check the manual for the

wccommand (either usingman wcorwc --help) to see if you can find out what flag to use to print out the number of words (but not the number of lines and bytes). Try it with the.csvfiles.If you have time, you can also try to sort the results by piping it to

sort. And/or explore the other flags ofwc.Solution

Using a Loop to Count Words

We will now use a loop to automate the counting of certain words within a document. For this, we will be using the Little Women e-book from Project Gutenberg. The file is inside the shell-lesson folder and named pg514.txt. Let’s rename the file to littlewomen.txt.

$ mv pg514.txt littlewomen.txt

This renames the file to something easier to type.

Now let’s create our loop. In the loop, we will ask the computer to go through the text, looking for each girl’s name, and count the number of times it appears. The results will print to the screen.

$ for name in "Jo" "Meg" "Beth" "Amy"

> do

> echo "$name"

> grep -wo "$name" littlewomen.txt | wc -l

> done

Jo

1355

Meg

683

Beth

459

Amy

645

What is happening in the loop?

echo "$name"is printing the current value of$namegrep "$name" littlewomen.txtfinds each line that contains the value stored in$name. The-wflag finds only the whole word that is the value stored in$nameand the-oflag pulls this value out from the line it is in to give you the actual words to count as lines in themselves.- The output from the

grepcommand is redirected with the pipe,|(without the pipe and the rest of the line, the output fromgrepwould print directly to the screen) wc -lcounts the number of lines (because we used the-lflag) sent fromgrep. Becausegreponly returned lines that contained the value stored in$name,wc -lcorresponds to the number of occurrences of each girl’s name.

Why are the variables double-quoted here?

a) In episode 4 we learned to use

"$..."as a safeguard against white-space being misinterpreted. Why could we omit the"-quotes in the above example?b) What happens if you add

"Louisa May Alcott"to the first line of the loop and remove the"from$namein the loop’s code?Solutions

Key Points

The shell can be used to count elements of documents

The shell can be used to search for patterns within files

Commands can be used to count and mine any number of files

Commands and flags can be combined to build complex queries specific to your work