Starting With Data

Last updated on 2024-07-11 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How can I import data in Python?

- What is Pandas?

- Why should I use Pandas to work with data?

Objectives

- Navigate the workshop directory and download a dataset.

- Explain what a library is and what libraries are used for.

- Describe what the Python Data Analysis Library (Pandas) is.

- Load the Python Data Analysis Library (Pandas).

- Read tabular data into Python using Pandas.

- Describe what a DataFrame is in Python.

- Access and summarize data stored in a DataFrame.

- Define indexing as it relates to data structures.

- Perform basic mathematical operations and summary statistics on data in a Pandas DataFrame.

- Create simple plots.

Working With Pandas DataFrames in Python

We can automate the process of performing data manipulations in Python. It’s efficient to spend time building the code to perform these tasks because once it’s built, we can use it over and over on different datasets that use a similar format. This makes our data manipulation processes reproducible. We can also share our code with colleagues and they can replicate the same analysis starting with the same original data.

Starting in the same spot

To help the lesson run smoothly, let’s ensure everyone is in the same directory. This should help us avoid path and file name issues. At this time please navigate to the workshop directory. If you are working in Jupyter Notebook be sure that you start your notebook in the workshop directory.

Our Data

For this lesson, we will be using the Portal Teaching data, a subset of the data from Ernst et al. Long-term monitoring and experimental manipulation of a Chihuahuan Desert ecosystem near Portal, Arizona, USA.

We will be using files from the Portal

Project Teaching Database. This section will use the

surveys.csv file that can be downloaded here: https://ndownloader.figshare.com/files/2292172

We are studying the species and

weight of animals caught in sites in our study area.

The dataset is stored as a .csv file: each row holds

information for a single animal, and the columns represent:

| Column | Description |

|---|---|

| record_id | Unique id for the observation |

| month | month of observation |

| day | day of observation |

| year | year of observation |

| plot_id | ID of a particular site |

| species_id | 2-letter code |

| sex | sex of animal (“M”, “F”) |

| hindfoot_length | length of the hindfoot in mm |

| weight | weight of the animal in grams |

The first few rows of our first file look like this:

OUTPUT

record_id,month,day,year,plot_id,species_id,sex,hindfoot_length,weight

1,7,16,1977,2,NL,M,32,

2,7,16,1977,3,NL,M,33,

3,7,16,1977,2,DM,F,37,

4,7,16,1977,7,DM,M,36,

5,7,16,1977,3,DM,M,35,

6,7,16,1977,1,PF,M,14,

7,7,16,1977,2,PE,F,,

8,7,16,1977,1,DM,M,37,

9,7,16,1977,1,DM,F,34,About Libraries

A library in Python contains a set of tools (called functions) that perform tasks on our data. Importing a library is like getting a piece of lab equipment out of a storage locker and setting it up on the bench for use in a project. Once a library is set up, it can be used or called to perform the task(s) it was built to do.

Pandas in Python

One of the best options for working with tabular data in Python is to use the Python Data Analysis Library (a.k.a. Pandas). The Pandas library provides data structures, produces high quality plots with matplotlib and integrates nicely with other libraries that use NumPy (which is another Python library) arrays.

Python doesn’t load all of the libraries available to it by default.

We have to add an import statement to our code in order to

use library functions. To import a library, we use the syntax

import libraryName. If we want to give the library a

nickname to shorten the command, we can add

as nickNameHere. An example of importing the pandas library

using the common nickname pd is below.

Each time we call a function that’s in a library, we use the syntax

LibraryName.FunctionName. Adding the library name with a

. before the function name tells Python where to find the

function. In the example above, we have imported Pandas as

pd. This means we don’t have to type out

pandas each time we call a Pandas function.

Reading CSV Data Using Pandas

We will begin by locating and reading our survey data which are in

CSV format. CSV stands for Comma-Separated Values and is a common way to

store formatted data. Other symbols may also be used, so you might see

tab-separated, colon-separated or space separated files. pandas can work

with each of these types of separators, as it allows you to specify the

appropriate separator for your data. CSV files (and other -separated

value file types) make it easy to share data, and can be imported and

exported from many applications, including Microsoft Excel. For more

details on CSV files, see the Data

Organisation in Spreadsheets lesson. We can use Pandas’

read_csv function to pull the file directly into a DataFrame.

So What’s a DataFrame?

A DataFrame is a 2-dimensional data structure that can store data of

different types (including strings, numbers, categories and more) in

columns. It is similar to a spreadsheet or an SQL table or the

data.frame in R. A DataFrame always has an index (0-based).

An index refers to the position of an element in the data structure.

PYTHON

# Note that pd.read_csv is used because we imported pandas as pd

pd.read_csv("data/surveys.csv")Finding the path. Why am I getting an “FileNotFoundError” message?

After running the previous command, you may encounter a red error message that says “FileNotFoundError”, and at the very end of it says “[Errno 2] No such file or directory: ‘data/surveys.csv’”. This error occurs when an incorrect path to the file is specified.

Jupyter typically uses the location of your notebook file (.ipynb) as the working directory for reading and writing files. Let’s assume you organized your project folder as recommended in Episode 1, like the following tree shows:

python-workshop

└───code

│ └───ep2_starting_with_data.ipynb

└───data

│ └───surveys.csv

└───documentsIn this scenario, when I run

pd.read_csv("data/surveys.csv") in my

ep2_starting_with_data.ipynb notebook, Python will look for

the file in the directory

python-workshop/code/data/surveys.csv, because my working

directory is where my notebook is located (i.e. inside the

code folder).

To specify the correct path from my working directory, I need to add

“../” to the start of my path. Therefore, the correct command would be

pd.read_csv("../data/surveys.csv"). “..” is a special

directory name meaning “the directory containing this one”, or more

succinctly, the parent of the current directory. With the path as

"../data/surveys.csv", I am first going to the parent

directory, which is “python-workshop” in this case, after that to the

“data” folder, and after that to the “survey.csv” file.

For future reference, if you need to know your working directory, you can use the built-in Python module “os” and its function “getcwd()”, like the following block shows:

The above command yields the output below:

OUTPUT

record_id month day year plot_id species_id sex hindfoot_length weight

0 1 7 16 1977 2 NL M 32.0 NaN

1 2 7 16 1977 3 NL M 33.0 NaN

2 3 7 16 1977 2 DM F 37.0 NaN

3 4 7 16 1977 7 DM M 36.0 NaN

4 5 7 16 1977 3 DM M 35.0 NaN

... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ...

35544 35545 12 31 2002 15 AH NaN NaN NaN

35545 35546 12 31 2002 15 AH NaN NaN NaN

35546 35547 12 31 2002 10 RM F 15.0 14.0

35547 35548 12 31 2002 7 DO M 36.0 51.0

35548 35549 12 31 2002 5 NaN NaN NaN NaN

[35549 rows x 9 columns]We can see that there were 35,549 rows parsed. Each row has 9

columns. The first column is the index of the DataFrame. The index is

used to identify the position of the data, but it is not an actual

column of the DataFrame. It looks like the read_csv

function in Pandas read our file properly. However, we haven’t saved any

data to memory so we can work with it. We need to assign the DataFrame

to a variable. Remember that a variable is a name for a value, such as

x, or data. We can create a new object with a

variable name by assigning a value to it using =.

Let’s call the imported survey data surveys_df:

Note that Python does not produce any output on the screen when you

assign the imported DataFrame to a variable. We can view the value of

the surveys_df object by typing its name into the Python

command prompt.

which prints contents like above.

Note: if the output is too wide to print on your narrow terminal window, you may see something slightly different as the large set of data scrolls past. You may see simply the last column of data:

OUTPUT

17 NaN

18 NaN

19 NaN

20 NaN

21 NaN

22 NaN

23 NaN

24 NaN

25 NaN

26 NaN

27 NaN

28 NaN

29 NaN

... ...

35519 36.0

35520 48.0

35521 45.0

35522 44.0

35523 27.0

35524 26.0

35525 24.0

35526 43.0

35527 NaN

35528 25.0

35529 NaN

35530 NaN

35531 43.0

35532 48.0

35533 56.0

35534 53.0

35535 42.0

35536 46.0

35537 31.0

35538 68.0

35539 23.0

35540 31.0

35541 29.0

35542 34.0

35543 NaN

35544 NaN

35545 NaN

35546 14.0

35547 51.0

35548 NaN

[35549 rows x 9 columns]Don’t worry: all the data is there! You can confirm this by scrolling

upwards, or by looking at the [# of rows x # of columns]

block at the end of the output.

You can also use surveys_df.head() to view only the

first few rows of the dataset in an output that is easier to fit in one

window. After doing this, you can see that pandas has neatly formatted

the data to fit our screen:

PYTHON

surveys_df.head() # The head() method displays the first several lines of a file. It

# is discussed below.OUTPUT

record_id month day year plot_id species_id sex hindfoot_length \

5 6 7 16 1977 1 PF M 14.0

6 7 7 16 1977 2 PE F NaN

7 8 7 16 1977 1 DM M 37.0

8 9 7 16 1977 1 DM F 34.0

9 10 7 16 1977 6 PF F 20.0

weight

5 NaN

6 NaN

7 NaN

8 NaN

9 NaNExploring Our Species Survey Data

A first good command to explore our dataset is the “info()” DataFrame method. It will show us useful information like: the number of rows (or entries) and columns in our dataset; and the name, number of non-null values and data type of each column.

OUTPUT

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 35549 entries, 0 to 35548

Data columns (total 9 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 record_id 35549 non-null int64

1 month 35549 non-null int64

2 day 35549 non-null int64

3 year 35549 non-null int64

4 plot_id 35549 non-null int64

5 species_id 34786 non-null object

6 sex 33038 non-null object

7 hindfoot_length 31438 non-null float64

8 weight 32283 non-null float64

dtypes: float64(2), int64(5), object(2)

memory usage: 2.4+ MBAgain, we can use the type function to see what kind of

thing surveys_df is:

OUTPUT

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>As expected, it’s a DataFrame (or, to use the full name that Python

uses to refer to it internally, a

pandas.core.frame.DataFrame).

What kind of things does surveys_df contain? DataFrames

have an attribute called dtypes that answers this:

OUTPUT

record_id int64

month int64

day int64

year int64

plot_id int64

species_id object

sex object

hindfoot_length float64

weight float64

dtype: objectAll the values in a single column have the same type. For example,

values in the month column have type int64, which is a kind

of integer. Cells in the month column cannot have fractional values, but

values in weight and hindfoot_length columns can, because they have type

float64. The object type doesn’t have a very

helpful name, but in this case it represents strings (such as ‘M’ and

‘F’ in the case of sex).

We’ll talk a bit more about what the different formats mean in a different lesson.

Useful Ways to View DataFrame Objects in Python

There are many ways to summarize and access the data stored in DataFrames, using attributes and methods provided by the DataFrame object.

Attributes are features of an object. For example, the

shape attribute will output the size (the number of rows

and columns) of an object. To access an attribute, use the DataFrame

object name followed by the attribute name

df_object.attribute. For example, using the DataFrame

surveys_df and attribute columns, an index of

all the column names in the DataFrame can be accessed with

surveys_df.columns.

Methods are like functions, but they only work on particular kinds of

objects. As an example, the head() method

works on DataFrames. Methods are called in a similar fashion to

attributes, using the syntax df_object.method(). Using

surveys_df.head() gets the first few rows in the DataFrame

surveys_df using the head() method. With a

method, we can supply extra information in the parentheses to control

behaviour.

Let’s look at the data using these.

Challenge - DataFrames

Using our DataFrame surveys_df, try out the

attributes & methods below to see

what they return.

surveys_df.columnssurveys_df.shapeTake note of the output ofshape- what format does it return the shape of the DataFrame in?

HINT: More on tuples, here.

surveys_df.head()Also, what doessurveys_df.head(15)do?surveys_df.tail()

-

surveys_df.columnsprovides the names of the columns in the DataFrame. -

surveys_df.shapeprovides the dimensions of the DataFrame as a tuple in(r,c)format, whereris the number of rows andcthe number of columns. -

surveys_df.head()returns the first 5 lines of the DataFrame, annotated with column and row labels. Adding an integer as an argument to the function specifies the number of lines to display from the top of the DataFrame, e.g.surveys_df.head(15)will return the first 15 lines. -

surveys_df.tail()will display the last 5 lines, and behaves similarly to thehead()method.

Calculating Statistics From Data In A Pandas DataFrame

We’ve read our data into Python. Next, let’s perform some quick summary statistics to learn more about the data that we’re working with. We might want to know how many animals were collected in each site, or how many of each species were caught. We can perform summary stats quickly using groups. But first we need to figure out what we want to group by.

Let’s begin by exploring our data:

which returns:

OUTPUT

Index(['record_id', 'month', 'day', 'year', 'plot_id', 'species_id', 'sex',

'hindfoot_length', 'weight'],

dtype='object')Let’s get a list of all the species. The pd.unique

function tells us all of the unique values in the

species_id column.

which returns:

OUTPUT

array(['NL', 'DM', 'PF', 'PE', 'DS', 'PP', 'SH', 'OT', 'DO', 'OX', 'SS',

'OL', 'RM', nan, 'SA', 'PM', 'AH', 'DX', 'AB', 'CB', 'CM', 'CQ',

'RF', 'PC', 'PG', 'PH', 'PU', 'CV', 'UR', 'UP', 'ZL', 'UL', 'CS',

'SC', 'BA', 'SF', 'RO', 'AS', 'SO', 'PI', 'ST', 'CU', 'SU', 'RX',

'PB', 'PL', 'PX', 'CT', 'US'], dtype=object)Challenge - Statistics

Create a list of unique site IDs (“plot_id”) found in the surveys data. Call it

site_names. How many unique sites are there in the data? How many unique species are in the data?What is the difference between

len(site_names)andsurveys_df['plot_id'].nunique()?

site_names = pd.unique(surveys_df["plot_id"])

- How many unique sites are in the data?

site_names.sizeorlen(site_names)provide the answer: 24 - How many unique species are in the data?

len(pd.unique(surveys_df["species_id"]))tells us there are 49 species

-

len(site_names)andsurveys_df['plot_id'].nunique()both provide the same output: they are alternative ways of getting the unique values. Thenuniquemethod combines the count and unique value extraction, and can help avoid the creation of intermediate variables likesite_names.

Groups in Pandas

We often want to calculate summary statistics grouped by subsets or attributes within fields of our data. For example, we might want to calculate the average weight of all individuals per site.

We can calculate basic statistics for all records in a single column using the syntax below:

gives output

PYTHON

count 32283.000000

mean 42.672428

std 36.631259

min 4.000000

25% 20.000000

50% 37.000000

75% 48.000000

max 280.000000

Name: weight, dtype: float64We can also extract one specific metric if we wish:

PYTHON

surveys_df['weight'].min()

surveys_df['weight'].max()

surveys_df['weight'].mean()

surveys_df['weight'].std()

surveys_df['weight'].count()But if we want to summarize by one or more variables, for example

sex, we can use Pandas’ .groupby method.

Once we’ve created a groupby DataFrame, we can quickly calculate summary

statistics by a group of our choice.

The pandas function describe will

return descriptive stats including: mean, median, max, min, std and

count for a particular column in the data. Pandas’ describe

function will only return summary values for columns containing numeric

data.

PYTHON

# Summary statistics for all numeric columns by sex

grouped_data.describe()

# Provide the mean for each numeric column by sex

grouped_data.mean(numeric_only=True)grouped_data.mean(numeric_only=True)

OUTPUT:

OUTPUT

record_id month day year plot_id \

sex

F 18036.412046 6.583047 16.007138 1990.644997 11.440854

M 17754.835601 6.392668 16.184286 1990.480401 11.098282

hindfoot_length weight

sex

F 28.836780 42.170555

M 29.709578 42.995379

The groupby command is powerful in that it allows us to

quickly generate summary stats.

Challenge - Summary Data

- How many recorded individuals are female

Fand how many maleM? - What happens when you group by two columns using the following syntax and then calculate mean values?

grouped_data2 = surveys_df.groupby(['plot_id', 'sex'])grouped_data2.mean(numeric_only=True)

- Summarize weight values for each site in your data. HINT: you can

use the following syntax to only create summary statistics for one

column in your data.

by_site['weight'].describe()

- The first column of output from

grouped_data.describe()(count) tells us that the data contains 15690 records for female individuals and 17348 records for male individuals.- Note that these two numbers do not sum to 35549, the total number of

rows we know to be in the

surveys_dfDataFrame. Why do you think some records were excluded from the grouping?

- Note that these two numbers do not sum to 35549, the total number of

rows we know to be in the

- Calling the

mean()method on data grouped by these two columns calculates and returns the mean value for each combination of plot and sex.- Note that the mean is not meaningful for some variables, e.g. day,

month, and year. You can specify particular columns and particular

summary statistics using the

agg()method (short for aggregate), e.g. to obtain the last survey year, median foot-length and mean weight for each plot/sex combination:

- Note that the mean is not meaningful for some variables, e.g. day,

month, and year. You can specify particular columns and particular

summary statistics using the

PYTHON

surveys_df.groupby(['plot_id', 'sex']).agg({"year": 'max',

"hindfoot_length": 'median',

"weight": 'mean'})surveys_df.groupby(['plot_id'])['weight'].describe()

OUTPUT

count mean std min 25% 50% 75% max

plot_id

1 1903.0 51.822911 38.176670 4.0 30.0 44.0 53.0 231.0

2 2074.0 52.251688 46.503602 5.0 24.0 41.0 50.0 278.0

3 1710.0 32.654386 35.641630 4.0 14.0 23.0 36.0 250.0

4 1866.0 47.928189 32.886598 4.0 30.0 43.0 50.0 200.0

5 1092.0 40.947802 34.086616 5.0 21.0 37.0 48.0 248.0

6 1463.0 36.738893 30.648310 5.0 18.0 30.0 45.0 243.0

7 638.0 20.663009 21.315325 4.0 11.0 17.0 23.0 235.0

8 1781.0 47.758001 33.192194 5.0 26.0 44.0 51.0 178.0

9 1811.0 51.432358 33.724726 6.0 36.0 45.0 50.0 275.0

10 279.0 18.541219 20.290806 4.0 10.0 12.0 21.0 237.0

11 1793.0 43.451757 28.975514 5.0 26.0 42.0 48.0 212.0

12 2219.0 49.496169 41.630035 6.0 26.0 42.0 50.0 280.0

13 1371.0 40.445660 34.042767 5.0 20.5 33.0 45.0 241.0

14 1728.0 46.277199 27.570389 5.0 36.0 44.0 49.0 222.0

15 869.0 27.042578 35.178142 4.0 11.0 18.0 26.0 259.0

16 480.0 24.585417 17.682334 4.0 12.0 20.0 34.0 158.0

17 1893.0 47.889593 35.802399 4.0 27.0 42.0 50.0 216.0

18 1351.0 40.005922 38.480856 5.0 17.5 30.0 44.0 256.0

19 1084.0 21.105166 13.269840 4.0 11.0 19.0 27.0 139.0

20 1222.0 48.665303 50.111539 5.0 17.0 31.0 47.0 223.0

21 1029.0 24.627794 21.199819 4.0 10.0 22.0 31.0 190.0

22 1298.0 54.146379 38.743967 5.0 29.0 42.0 54.0 212.0

23 369.0 19.634146 18.382678 4.0 10.0 14.0 23.0 199.0

24 960.0 43.679167 45.936588 4.0 19.0 27.5 45.0 251.0Quickly Creating Summary Counts in Pandas

Let’s next count the number of samples for each species. We can do

this in a few ways, but we’ll use groupby combined with

a count() method.

PYTHON

# Count the number of samples by species

species_counts = surveys_df.groupby('species_id')['record_id'].count()

print(species_counts)Or, we can also count just the rows that have the species “DO”:

Challenge - Make a list

What’s another way to create a list of species and associated

count of the records in the data? Hint: you can perform

count, min, etc. functions on groupby

DataFrames in the same way you can perform them on regular

DataFrames.

As well as calling count() on the record_id

column of the grouped DataFrame as above, an equivalent result can be

obtained by extracting record_id from the result of

count() called directly on the grouped DataFrame:

OUTPUT

species_id

AB 303

AH 437

AS 2

BA 46

CB 50

CM 13

CQ 16

CS 1

CT 1

CU 1

CV 1

DM 10596

DO 3027

DS 2504

DX 40

NL 1252

OL 1006

OT 2249

OX 12

PB 2891

PC 39

PE 1299

PF 1597

PG 8

PH 32

PI 9

PL 36

PM 899

PP 3123

PU 5

PX 6

RF 75

RM 2609

RO 8

RX 2

SA 75

SC 1

SF 43

SH 147

SO 43

SS 248

ST 1

SU 5

UL 4

UP 8

UR 10

US 4

ZL 2Basic Math Functions

If we wanted to, we could apply a mathematical operation like addition or division on an entire column of our data. For example, let’s multiply all weight values by 2.

A more practical use of this might be to normalize the data according to a mean, area, or some other value calculated from our data.

Quick & Easy Plotting Data Using Pandas

We can plot our summary stats using Pandas, too.

PYTHON

# Make sure figures appear inline in Ipython Notebook

%matplotlib inline

# Create a quick bar chart

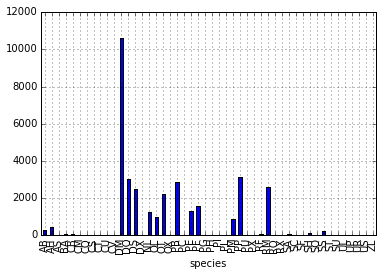

species_counts.plot(kind='bar'); Count per species site

Count per species site

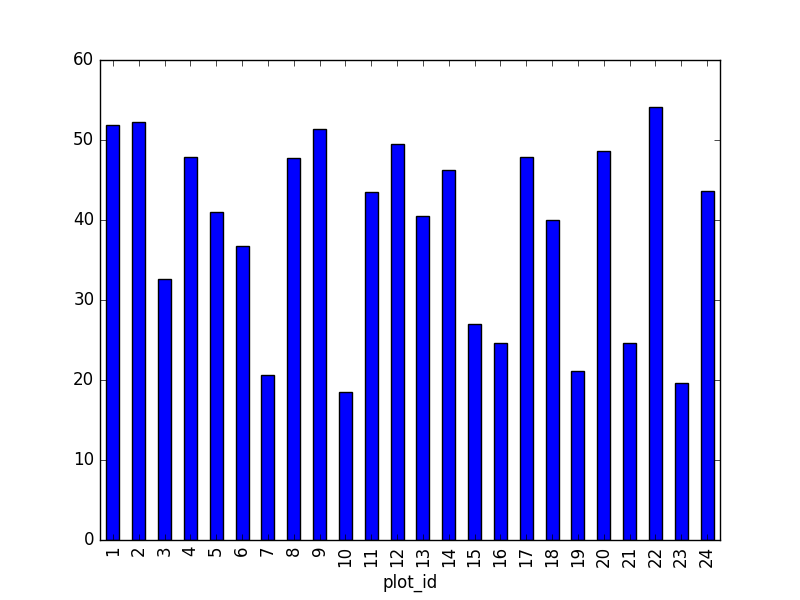

We can also look at how many animals were captured in each site:

PYTHON

total_count = surveys_df.groupby('plot_id')['record_id'].nunique()

# Let's plot that too

total_count.plot(kind='bar');Challenge - Plots

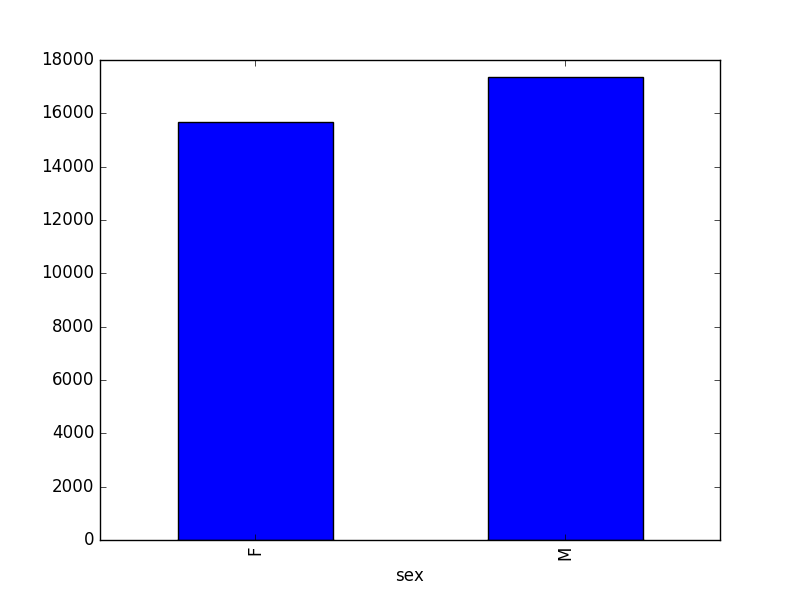

- Create a plot of average weight across all species per site.

- Create a plot of total males versus total females for the entire dataset.

surveys_df.groupby('plot_id').mean()["weight"].plot(kind='bar')

surveys_df.groupby('sex').count()["record_id"].plot(kind='bar')

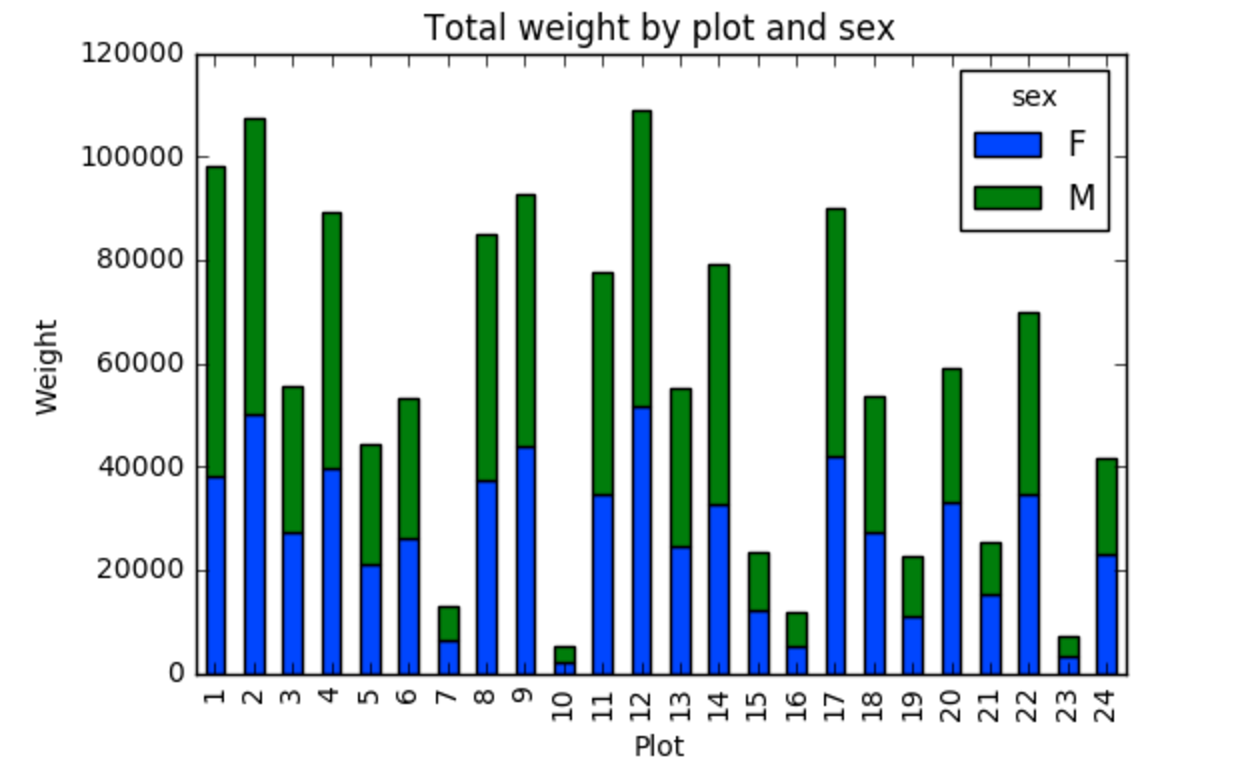

Summary Plotting Challenge

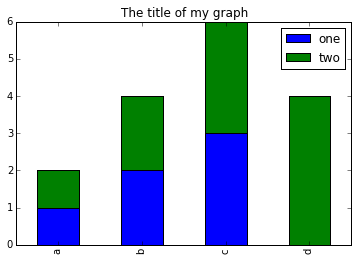

Create a stacked bar plot, with weight on the Y axis, and the stacked variable being sex. The plot should show total weight by sex for each site. Some tips are below to help you solve this challenge:

- For more information on pandas plots, see pandas’ documentation page on visualization.

- You can use the code that follows to create a stacked bar plot but the data to stack need to be in individual columns. Here’s a simple example with some data where ‘a’, ‘b’, and ‘c’ are the groups, and ‘one’ and ‘two’ are the subgroups.

PYTHON

d = {'one' : pd.Series([1., 2., 3.], index=['a', 'b', 'c']), 'two' : pd.Series([1., 2., 3., 4.], index=['a', 'b', 'c', 'd'])}

pd.DataFrame(d)shows the following data

OUTPUT

one two

a 1 1

b 2 2

c 3 3

d NaN 4We can plot the above with

PYTHON

# Plot stacked data so columns 'one' and 'two' are stacked

my_df = pd.DataFrame(d)

my_df.plot(kind='bar', stacked=True, title="The title of my graph")

- You can use the

.unstack()method to transform grouped data into columns for each plotting. Try running.unstack()on some DataFrames above and see what it yields.

Start by transforming the grouped data (by site and sex) into an unstacked layout, then create a stacked plot.

First we group data by site and by sex, and then calculate a total for each site.

PYTHON

by_site_sex = surveys_df.groupby(['plot_id', 'sex'])

site_sex_count = by_site_sex['weight'].sum()This calculates the sums of weights for each sex within each site as a table

OUTPUT

site sex

plot_id sex

1 F 38253

M 59979

2 F 50144

M 57250

3 F 27251

M 28253

4 F 39796

M 49377

<other sites removed for brevity>Below we’ll use .unstack() on our grouped data to figure

out the total weight that each sex contributed to each site.

PYTHON

by_site_sex = surveys_df.groupby(['plot_id', 'sex'])

site_sex_count = by_site_sex['weight'].sum()

site_sex_count.unstack()The unstack method above will display the following

output:

OUTPUT

sex F M

plot_id

1 38253 59979

2 50144 57250

3 27251 28253

4 39796 49377

<other sites removed for brevity>Now, create a stacked bar plot with that data where the weights for each sex are stacked by site.

Rather than display it as a table, we can plot the above data by stacking the values of each sex as follows:

PYTHON

by_site_sex = surveys_df.groupby(['plot_id', 'sex'])

site_sex_count = by_site_sex['weight'].sum()

spc = site_sex_count.unstack()

s_plot = spc.plot(kind='bar', stacked=True, title="Total weight by site and sex")

s_plot.set_ylabel("Weight")

s_plot.set_xlabel("Plot")

Key Points

- Libraries enable us to extend the functionality of Python.

- Pandas is a popular library for working with data.

- A Dataframe is a Pandas data structure that allows one to access data by column (name or index) or row.

- Aggregating data using the

groupby()function enables you to generate useful summaries of data quickly. - Plots can be created from DataFrames or subsets of data that have

been generated with

groupby().