Introduction

Overview

Teaching: 5 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What is version control and why should I use it?

Objectives

Understand the benefits of an automated version control system.

Understand the basics of how automated version control systems work.

Explain how the shell relates to the keyboard, the screen, the operating system, and users’ programs.

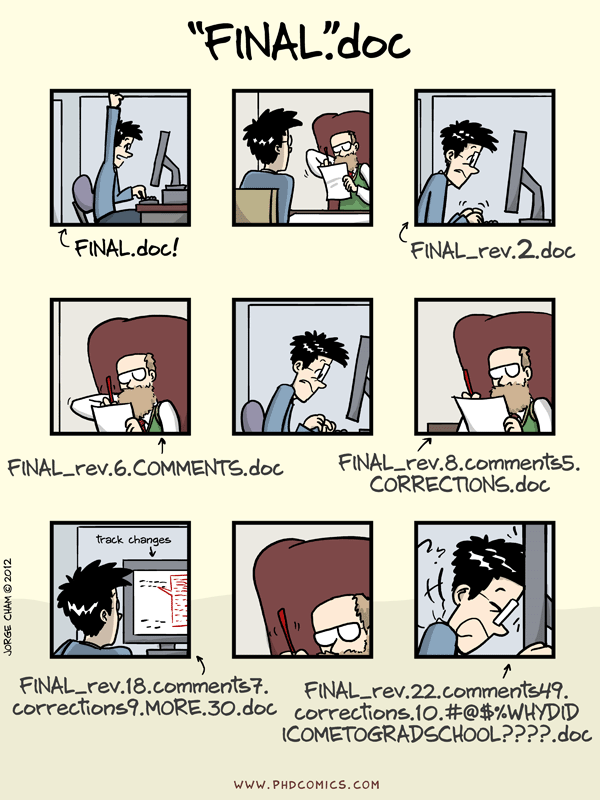

We’ll start by exploring how version control can be used to keep track of what one person did and when. Even if you aren’t collaborating with other people, automated version control is much better than this situation:

“Piled Higher and Deeper” by Jorge Cham, http://www.phdcomics.com

We’ve all been in this situation before: it seems ridiculous to have multiple nearly-identical versions of the same document. Some word processors let us deal with this a little better, such as Microsoft Word’s Track Changes, Google Docs’ version history, or LibreOffice’s Recording and Displaying Changes.

Version control systems start with a base version of the document and then record changes you make each step of the way. You can think of it as a recording of your progress: you can rewind to start at the base document and play back each change you made, eventually arriving at your more recent version.

Once you think of changes as separate from the document itself, you can then think about “playing back” different sets of changes on the base document, ultimately resulting in different versions of that document. For example, two users can make independent sets of changes on the same document.

Unless multiple users make changes to the same section of the document - a conflict - you can incorporate two sets of changes into the same base document.

A version control system is a tool that keeps track of these changes for us, effectively creating different versions of our files. It allows us to decide which changes will be made to the next version (each record of these changes is called a commit), and keeps useful metadata about them. The complete history of commits for a particular project and their metadata make up a repository. Repositories can be kept in sync across different computers, facilitating collaboration among different people.

To build this workshop’s website, we often have multiple people working on the site independantly. Here is a snapshot of the history of changes, or commits, which we have implemented on this website. You will notice multiple people are involved, and they each include a comment on what changes are being made.

Taking a closer look at one of these commits, we can see what exactly has been edited. The line of content which has been changed is marked in red, and the new line of content is marked in green.

The Long History of Version Control Systems

Automated version control systems are nothing new. Tools like RCS, CVS, or Subversion have been around since the early 1980s and are used by many large companies. However, many of these are now considered legacy systems (i.e., outdated) due to various limitations in their capabilities. More modern systems, such as Git and Mercurial, are distributed, meaning that they do not need a centralized server to host the repository. These modern systems also include powerful merging tools that make it possible for multiple authors to work on the same files concurrently.

Paper Writing

Imagine you drafted an excellent paragraph for a paper you are writing, but later ruin it. How would you retrieve the excellent version of your conclusion? Is it even possible?

Imagine you have 5 co-authors. How would you manage the changes and comments they make to your paper? If you use LibreOffice Writer or Microsoft Word, what happens if you accept changes made using the

Track Changesoption? Do you have a history of those changes?Solution

Recovering the excellent version is only possible if you created a copy of the old version of the paper. The danger of losing good versions often leads to the problematic workflow illustrated in the PhD Comics cartoon at the top of this page.

Collaborative writing with traditional word processors is cumbersome. Either every collaborator has to work on a document sequentially (slowing down the process of writing), or you have to send out a version to all collaborators and manually merge their comments into your document. The ‘track changes’ or ‘record changes’ option can highlight changes for you and simplifies merging, but as soon as you accept changes you will lose their history. You will then no longer know who suggested that change, why it was suggested, or when it was merged into the rest of the document. Even online word processors like Google Docs or Microsoft Office Online do not fully resolve these problems.

The Shell

Git is a command line tool, so we’ll start the workshop with an introduction to working with “the shell”. The shell is a program where users can type commands. With the shell, it’s possible to invoke complicated programs like climate modeling software or simple commands that create an empty directory with only one line of code. The most popular Unix shell is Bash (the Bourne Again SHell — so-called because it’s derived from a shell written by Stephen Bourne). Bash is the default shell on most modern implementations of Unix and in most packages that provide Unix-like tools for Windows.

Using the shell will take some effort and some time to learn. While a GUI presents you with choices to select, CLI choices are not automatically presented to you, so you must learn a few commands like new vocabulary in a language you’re studying. However, unlike a spoken language, a small number of “words” (i.e. commands) gets you a long way, and we’ll cover those essential few today.

The grammar of a shell allows you to combine existing tools into powerful pipelines and handle large volumes of data automatically. Sequences of commands can be written into a script, improving the reproducibility of workflows.

In addition, the command line is often the easiest way to interact with remote machines and supercomputers. Familiarity with the shell is near essential to run a variety of specialized tools and resources including high-performance computing systems. As clusters and cloud computing systems become more popular for scientific data crunching, being able to interact with the shell is becoming a necessary skill. We can build on the command-line skills covered here to tackle a wide range of scientific questions and computational challenges.

Let’s get started.

When the shell is first opened, you are presented with a prompt, indicating that the shell is waiting for input.

$

The shell typically uses $ as the prompt, but may use a different symbol.

In the examples for this lesson, we’ll show the prompt as $ .

Most importantly:

when typing commands, either from these lessons or from other sources,

do not type the prompt, only the commands that follow it.

Also note that after you type a command, you have to press the Enter key to execute it.

Changing your prompt

Your prompt may be super long (containing your username, computer name, etc.). To change your prompt type in:

$ export PS1= ">"This will last as long as the length of your shell session.

The prompt is followed by a text cursor, a character that indicates the position where your typing will appear. The cursor is usually a flashing or solid block, but it can also be an underscore or a pipe. You may have seen it in a text editor program, for example.

So let’s try our first command, ls which is short for listing.

This command will list the contents of the current directory:

$ ls

Desktop Downloads Movies Pictures

Documents Library Music Public

Command not found

If the shell can’t find a program whose name is the command you typed, it will print an error message such as:

$ ksks: command not foundThis might happen if the command was mis-typed or if the program corresponding to that command is not installed.

Key Points

Version control is like an unlimited ‘undo’.

Version control also allows many people to work in parallel.

A shell is a program whose primary purpose is to read commands and run other programs.